Until recently, there were limited options for an endurance athlete to get a handle on his or her metabolic response to exercise at varying intensities. There are several good options, but I’m going to focus on the ones we usually default to for determining the two thresholds that represent important metabolic shifts. Knowing these two points will set you up well for controlling the intensity of your training. Be aware that the first test requires serious technology, such as an expensive heart rate monitor/GPS watch. For the no-tech test, skip ahead to the Nose Breathing section. But the second test is as simple as can be. It’s just demanding.

Jump Ahead To:

ToggleTesting Aerobic Threshold (AeT)

Heart Rate Drift

After wearable heart rate monitors became widely available in the early 80s, astute coaches and athletes noticed that on runs over about 30-45 minutes, the runner’s heart rate might rise while they maintained the same pace or even if they slowed the pace. Coaches called this “heart rate drift”, but it was only understood qualitatively. With the advent of the newer generation of heart rate monitors combined with a GPS in the same watch, the analysis of the “drift” moved from being a qualitative oddity to becoming a quantifiable, valuable, and actionable piece of data.

If while holding the same pace, your heart rate climbs more than 5% during an hour of continuous exercise, OR if, while keeping your heart rate steady, your pace slows more than 5% during an hour of continuous exercise, the chances are excellent that you began that hour at a heart rate that was above your aerobic threshold (AeT) or the top of Zone 2.

From a metabolic standpoint, heart rate drift means your energy requirements exceed your aerobic capacity. As you know from this article, when your energy demands exceed your aerobic capacity, your anaerobic system must make up the difference. It is this anaerobic contribution to the overall energy requirement that is causing your heart rate to slowly drift up during that hour.

We have had extensive experience administering, interpreting, and evaluating HR drift tests for hundreds of athletes over six years. The HR drift test correlates very closely to the expensive laboratory-administered gas exchange test (GET) we’ll discuss shortly when establishing your AeT. Besides the money savings, it has the benefit of being able to be re-tested whenever you desire. More on that when we get into the testing in the next section. This has become our go-to test, even for our elite athletes, to establish the top of Z2.

How to conduct this test

Our first choice is to do this test on a treadmill or a StairMaster (these look like short escalators) for mountaineers. This allows closer control and fewer variables to deal with. Runners should do this running on a 2% grade. Those who can’t run should or will do most of their aerobic base training hiking and should set the treadmill to 15% and hike. Mountaineers can use either a treadmill set to 15% or a stair machine.

NOTE: If you’re using one of these machines, do not hang on to the handrails. You will not have bars when you go outside, and hanging on makes it too easy.

Indoors HR Drift test on a treadmill or stair machine:

- Warm up gradually for at least 10 minutes, never exceeding a nose breathing pace.

- During the warm-up, you can fiddle with the pace (while nose breathing) to establish a starting pace where your HR stabilizes in a range of plus-minus 2-3 beats around a number for at least 3 minutes. If your HR continues to climb during these 3 minutes, the pace is too fast. Slow it down till your HR stabilizes for 3-4 minutes. It is essential to let your HR stabilize at a pace before starting the test.

- After you find that stable HR pace, DO NOT TOUCH THE SPEED CONTROL FOR THE REST OF THE TEST. This is the most common mistake folks make. If, say, 10 minutes into the test, your HR is ten beats higher than the start and continuing to climb, the starting pace/HR was too high, and you will need to redo the test. Slowing the treadmill speed down during the test invalidates the result. It is probably best to come back another day to do the test again at a slower pace.

- If all is good, though, continue this test for 60 minutes. Some gyms limit treadmill time to 60min, so you may need to do all this fiddling around during the warm-up, stop the machine, start your watch over again, and record a new session so you can go an hour.

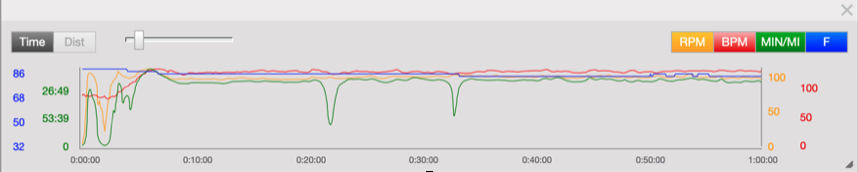

- By holding the treadmill speed constant, the only variable you need to consider is HR. Using a Training Peaks premium account, upload this workout, click the analyze button (upper right of the workout window), and see a graph like this one from a real HR drift test one of our athletes did. The red line is the HR data, the only data you need to look at.

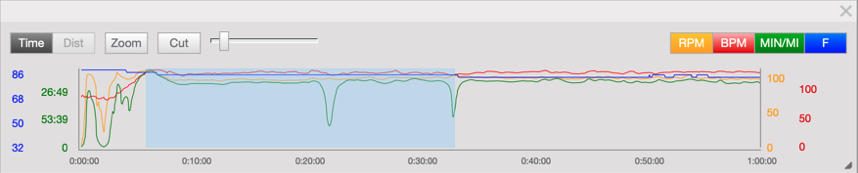

Using your cursor, select the first half of the session. In this graph, you would start that selection by dragging the cursor from about the 5min mark where the HR settled down till a bit past 30 minutes. It is not necessary to select the halves of the test exactly. Plus/minus a few minutes is fine. When you drag the cursor over the first half, you will see this:

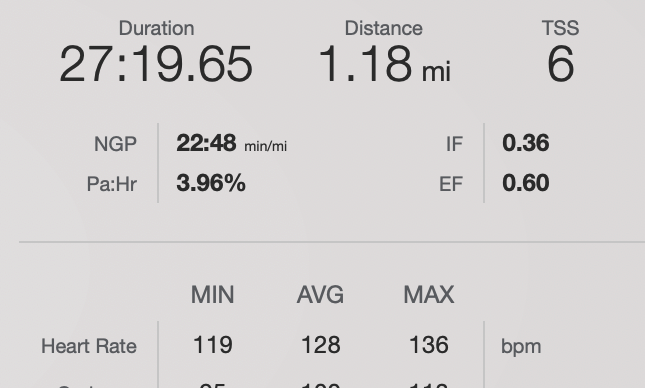

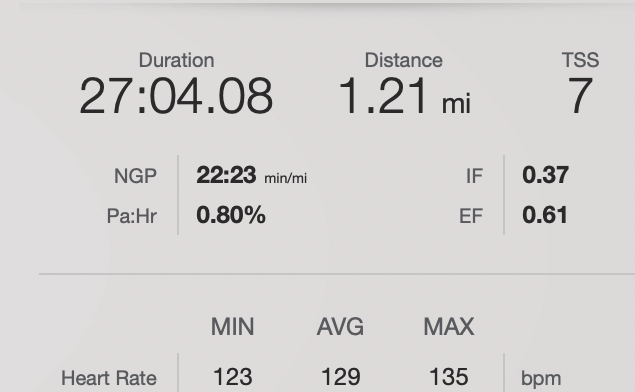

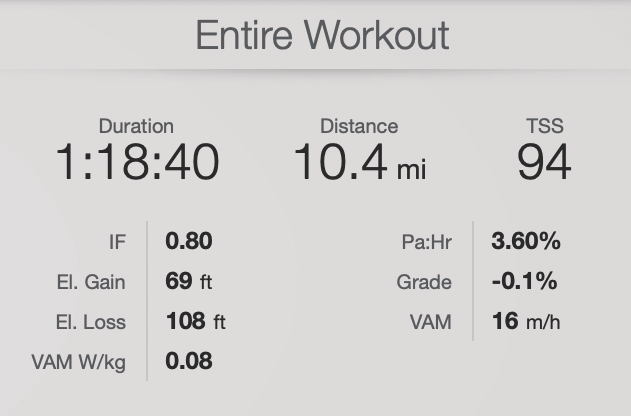

In the upper right of the Analyze screen, you will see the data for the selected portion.

You can disregard the Pa: Hr because the pace and distance are probably inaccurate because the GPS does not work indoors. But you will see that the average HR was 128 for this first half of the text. Doing the same thing for the second half will give you the average HR for the second half.

In this test, there was virtually no upward drift in HR. That tells us that the starting HR (about 127 in this case) was well under this athlete’s aerobic threshold. Because this test showed no drift, I would normally suggest the athlete redo the test with a starting HR of about 135.

Outside HR Drift Test for Running

Use a Training Peaks premium account to analyze your heart rate drift by clicking on the analyze button in the data displayed in the upper right corner. You will see Pa: Hr. That’s the HR drift. This test must be conducted on either a flat course like a running track or a gently rolling loop course with less than 100ft (30m) elevation change per mile (1.6km). DO NOT USE AN OUT-AND-BACK COURSE. Inevitably one way will be more uphill than the other, and the results will skew the test. It is impossible to do this test hiking on a natural gradient outdoors. You will not be able to find a consistent grade that continues for one hour.

Warm up with the same protocol as above. Find a comfortable nose breathing pace and start the test when you establish that. Upload the data to your Training Peaks premium account and click the “analyze” button. A screen like the one below will show, and Pa: Hr is the number you are looking at because your GPS works outdoors.

In this case, an outside running HR drift test of 3.6% indicates that he was within his aerobic capacity. Notice that over 10 miles, this run only gained and lost around 100ft.

Analyzing the Heart Rate Drift Test

Nose Breathing Test and Intensity Monitoring

This is the ultimate low-tech method of determining your AeT. Not only that, but it also has the best real-time feedback on your metabolic state outside of a lab…… IF YOU PAY CLOSE ATTENTION.

Exercise scientists call the rate and depth of breathing ventilation. With specialized equipment, they can measure how much air your lungs are pumping in and out each minute and the percentage of oxygen and CO2 in each breath.

You may have heard the terms “first and second ventilatory thresholds (VT1 and VT2)”. That same specialized lab equipment can pinpoint these points which occur at important metabolic events. We, laymen, can also get close to locating these points by carefully monitoring our ventilation (rate and depth of breathing). The first metabolic threshold you cross (VT1, often called the aerobic threshold) corresponds very closely for almost all of us with the upper limit of nose breathing or where you can speak in complete sentences.

VT2 corresponds to another noticeable jump in ventilation where you can only manage one or two words. Below this, breathing will be steady and deep but not labored. Above this point, you are in a state of hyperventilation where your body is trying desperately to blow off excess CO2. In the old days, we called this point break-away breathing.

For the perceptive athlete, there is a noticeable jump in ventilation at both these thresholds. Since they occur at significant metabolic points, it behooves you to notice them. That way, when you are out for a run, hike, or skin and you’ve forgotten your HR monitor, you will be able to determine your metabolic state. Are you in Zone 2 or pushing well into Z3 because you are forced to breathe through your mouth?

Be aware that your AeT and AnT heart rates will vary daily, depending on your recovery state. So by blindly adhering to heart rate, you may be overreaching by trying to hit your AeT HR when you are tired.

Whereas ventilation is a direct result of the metabolism fueling your exercise, paying attention to your breathing during your training will alert you to when your AeT is a bit lower on a day when you are tired. It is like having that fancy lab testing equipment with you during each run.

Gas Exchange Test

I used to call this the gold standard: A gas exchange test done in a laboratory and usually costing $200-$300. The best use for this test is to determine where you are getting the calories that propel you: Are they from fat or carbohydrates? This is best done with a metabolic efficiency test (MET), which only some testing labs are familiar with. Most labs will offer to have you do a maxVO2 test. The protocols for these two tests are quite different. For the MET, you should be in a fasted state. For the maxVO2, you must have eaten some carbohydrates within 30-60 minutes. There are other differences that I won’t go into here. If all you want to do is determine your aerobic threshold (AeT, top of Zone 2), this test is overkill. This test is for the uber-curious or the elite athlete who plans to get tested frequently at the same lab.

Blood Lactate Test

Long ago, this was my go-to test for determining AeT and checking if the skiers I was coaching were staying under AeT during long, easy workouts. But I needed to be there in person to test. You can test yourself. But this test is, again, for the curious who plan on frequent testing to control the progression of their training. It’s a bit overkill for most folks, and these lactate meters are a few hundred dollars. The test strips are also expensive. I have written an in-depth “how to” lactate test article that I will link to soon.

Over the past few decades, I have moved from basing training zones entirely on blood lactate tests or laboratory Gas Exchange Tests to the more straightforward but high-tech HR drift test, which still requires expensive equipment and a Training Peaks account. This is still the test we administer to all of our coached athletes. We confidently recommend it to anyone. However, there is something incredibly alluring about the no-tech nose breathing/ventilation test. It may tune you into your body even more than paying attention to your heart rate. Suppose you are going to experiment with the nose breathing test. In that case, we recommend that you do so with a heart rate monitor and learn to correlate these two physiological markers to each other and, most importantly, to how you feel.

Testing Anaeroibic Threshold (AnT)

I like to use this very simple, but in my view, the best test for determining the anaerobic threshold. The results of this test are the simplest to interpret, easiest to implement, and, therefore, most useful by a coach or athlete. This threshold, by any of its several names, is your endurance limit. The value you determine using this test, whether using heart rate, running pace, or power, will be an actual measure of the maximum work rate you can sustain for an extended length of time. Your AnT will likely vary under different conditions/events. A test running on the flats is probably not going to yield the same average heart rate as an uphill hike with a pack. These two will most certainly yield different average paces.

If this doesn’t seem “sciency” enough for you, consider an example:

- You execute your own “Vertical Kilometer” (VK) time trial on a steep local hill with a heavy pack. It is not necessary that it actually gain 1km in elevation but say it takes you 43 minutes going as hard as you can go, without blowing up, to gain 285m. Your average heart rate for the test was 168bpm, and your average rate of climb was 285m/43min or about 6.6m/min. These numbers represent the limit of your endurance on this hill with this weight pack.

This is as actionable as a piece of data can be and much more useful to a coach or athlete in terms of programming than a blood lactate test running on a treadmill would have been for determining AnT.

The test can be as short as 20 minutes for someone just starting out with this kind of training or up to an hour for a world-class athlete. All you are going to do is run, ski, cycle or hike steeply uphill as fast as you can for the alotted time. It will feel like a race or time trial. If you are careful not to start too hard and blow up 5 minutes into the test, your average heart rate, pace, or power is going to be the maximum you can sustain for that period. Bingo. It is that simple.

I prefer this to any other test because it is actually measuring your performance. It is not measuring a proxy for performance, such as interpreting the RER from a gas exchange test or trying to suss out where the blood lactate curves make that bend upward.

Warning: This test is hard and should only be conducted when you are well-rested if the results are going to be meaningful. Doing this test tired will still feel very hard, but the average heart rate and pace will be lower than in a rested state.

What to do with this information: The 10% Rule

Once you have conducted these two tests, you will have a decent snapshot of how your metabolism responds to exercise. That’s a powerful tool and can guide your training if you pay attention. By comparing the metabolic responses to exercise for an athlete before and after six months of the type of training we promote, we will be able to see how you can make the best use of the test info you just completed. While Bob is not his real name, this example is not fictitious. We see this kind of improvement in athletes we coach and hear from athletes training on their own.

On week one: Bob is 31 years old and has a busy work and family life. He has recently read Training for the Uphill Athlete and begun to train using the methods we promote. He has a high work capacity from playing ball sports through college and participating in 2-3 Crossfit workouts a week for the past three years. In the past, most of his running workouts have been done at a pace that was as fast as he could maintain for the time or distance he could squeeze in. If he had 30 minutes, he’d run as hard as he could for 30 minutes. If he had an hour, he’d run as hard as he could for that hour. He had the intensity needle pinned to the red zone for almost all his runs. The results of his heart rate drift test showed his aerobic threshold to be 136bpm at 11:30 min/mile (7:08 min/km), which he found to be a very easy effort. It was so easy that he was convinced that either he did the test wrong or we must be smoking something to suggest that training at this intensity could accomplish any training effect. After making sure that the test was correctly done, his Evoke coach explained to him that this result was, in fact, a good measure of his aerobic capacity. This was all the energy his aerobic system was capable of producing right now before the anaerobic or glycolytic metabolic system had to begin to provide more than about 50% of his energy needs.

Next came the anaerobic threshold test, an all-out 30-minute run where his average heart rate was 168 and his average pace was 9:20 minutes/mile (5:37min/km). The spread between his aerobic and anaerobic thresholds is 23.5% (in terms of heart rate; 169/136) and 23% in terms of his pace (11:30/9:20). Because of all the high-intensity training he had done in the past few years, his anaerobic system has a high capacity.

In setting his zones, we used his heart rate drift test to set the top of his Zone 2 and his anaerobic threshold test to set the top of his Zone 3. When we did that, we saw that his purely aerobic zones 1 and 2 were squeezed below 136 at what he felt was a silly slow speed. He had a very broad Zone 3 because his muscles required a heavy dose of glucose to provide the energy he needed. His anaerobic system was the predominant fuel source, even at slow speeds. To better understand why this is a problem for an endurance athlete and an ever bigger one for ultra-long events like many of us engage in, please read this article https://evokeendurance.com/endurance-its-evolution-psychology-meaning-physiology-and-how-to-improve-yours/

The best course of action for him is to concentrate his training efforts on elevating his aerobic threshold to bring his aerobic and anaerobic metabolisms into a better balance for his endurance goals. He is suffering from a condition we see all too often: Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome.

Six months later, after doing almost all of his aerobic training in Zone 2 and having retested his aerobic and anaerobic threshold every 4-6 weeks or whenever he or his coach noticed an increase in his running pace at his aerobic threshold, his metabolism has begun to transform into that of an endurance athlete. His heart rate drift test now gives his aerobic threshold as 155 bpm and 9:45 min/mile (6:15 min/km). His anaerobic threshold has not moved because his training has been focused on fixing his aerobic deficit. There have been no workouts yet that provide a training stimulus to his anaerobic system. But now his aerobic and anaerobic thresholds are only 8% apart in terms of heart rate and 4.5% in terms of pace. His Zone 3 has shrunk to where it is only 14 bpm wide compared to 33 bpm wide when he started training this way.

The performance implications of this are profound. His aerobic capacity has increased dramatically. He can now comfortably sustain a running pace that is within 5% of the pace that took a maximum effort six months ago. His aerobic system is now able to fuel a much higher speed before having to call in the reserves, which are the anaerobic cavalry. Now his aerobic deficiency has been dealt a death blow, the gloves have come off, and the more interesting performance-related training is set to begin. His coach will begin programming more Zone 3 and 4 workots which will elevate his anaerobic threshold heart rate and pace.

The good news for Bob is that he has done all this in just six months. And this is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of improving his endurance. While his aerobic threshold heart rate may not move up much more, his pace at that heart rate can continue to increase for several more years under this kind of training approach. Along with more intensity training, his anaerobic threshold pace will also move up substantially. This AnT pace is the best correlation with endurance performance.

Bob is a runner, but the same concepts, principles, methods, and results work with all endurance athletes.

10% Rule

This is not some formula derived from scientific studies. It comes from the observations of many elite athletes by their coaches. Elites have a very high aerobic threshold and a very small Zone 3. The difference between being in a full aerobic metabolic state (in Zone 2) and going as fast as they can sustain for several minutes at a time (Zone 4) is only a few beats per minute and a handful of seconds per mile or kilometer. When the spread between the aerobic and anaerobic threshold drops to 10% or less, the athlete is considered to have a well-developed aerobic base and should begin to introduce more high-intensity training and reduce the time spent in Zone 2 because the pace/effort is too demanding muscularly.

NOTE: Before any of you math nerds out there correct my percentage calculations, I know that this is not the proper way of calculating percentage differences. However, the difference is tiny and immaterial, and the simplicity of the above method makes it much quicker and easier to use.

Summary

The simplicity and free cost of these tests allow you to repeat them anytime you choose. At Evoke, our coaches have used these tests with hundreds of athletes over the past seven years.

As a nice gauge of fitness, I will sometimes have my athletes conduct a couple of time trials at the beginning of our training together and repeat the tests a few months later. One test is done at the AeT heart rate to gauge the progress in aerobic capacity. And one is done at the AnT heart rate to test their endurance. While you can use different courses for the AeT and AnT tests, be sure to repeat the tests on the same course(s) under similar conditions so you are comparing apples to apples.

Facebook

Facebook

Hi Scott,

first of all: Thank you so much for sharing your knowledge! When I came across your drift test the first time it was mind changing as it convinced me that I have to walk to train my aerobic system.

Meanwhile I have experimented with the test quite a bit and came across several puzzles. I guess you or the people in the Evoke Endurance community already know the answers to some of my questions. Otherwise maybe we can experiment together to generate knowledge and understand the test even better. 🙂

1) DRIFT TEST SHORT VERSION

Problem: For me (still unfit) the drift test as described has a relative high cost in terms of recovery. 10-20min warm up plus 60min test makes almost 1,5h training, most of the time close to the AeT.

Solution: To get around this problem I do a warm up until my HR stabilizes (mostly 15-20min) and then do 30min of constant heart rate. I walk a circuit that takes me 1-2min, stop every lap, fit a regression to the lap times, extrapolate the regression line to 60min and then compare my projected lap time after 60min to my lap time at the start.

Question: What are your ideas to make the test easier and suitable for untrained people?

2) CONSISTENT DRIFT FOR PACE (VS HEART RATE)

Puzzle: After some experimentation I found that my heart rate and one-hour-drift seem to be rather losely coupled, for example I got the same one-hour-drift for different starting heart rates. However, my starting pace seems to be very consistently coupled to the one-hour-drift.

Question: Would it be more precise to define AeT in terms of pace instead of hear rate? And how would you define your training zones in terms of pace? AeT-Pace minus 10%? Of course, if you leave flat ground pace does make much sense anymore, but as long as it is flat, should we rather train by pace?

3) MATCHING DRIFT TO TRAING ZONES

Puzzle: For me it took quite some poking in the haystack to find the 5% sweet spot. One day I thought the following: Basically we have two dimensions, one is effort, one is one-hour-drift. AeT-effort seems to match with 5% one-hour-drift.

Question: Can we maybe match other one-hour-drifts to the effort dimension? Perhaps 1% one-hour-drift is the bottom of zone Z1? Or 3% one-hour-drift correlates with the bottom of zone Z2? Unfortunately, I don’t have enough data to deduce such equivalences between starting-effort and one-hour-drift. But maybe some people know their one-hour-drift at Z1? I’d be curious about it!

4) NEGATIVE DRIFT

Puzzle: Finally, if I walk very slowly I get a negative one-hour-drift of 10%-20%, despite warming up 15-20min (so the aerobic system should be online). Also my lap times keep getting faster until the end of the test, so it does not seem to be a warm-up effect.

Question: Have you observed or experienced similar results? What could be the physiological reason? Maybe an increasingly suppressed heart rate that makes me increase speed during the test to keep HR constant? Or is it maybe a relaxation effect that calms the sympaticus (I find these slow walks very calming, it feels like meditation)?

I am so happy about the existence of the book “Training for the uphill athlete” and this site. Unfortunately I had to turn 37 to learn such fundamental things about my body. But better late than never! 🙂

Kind regards

Christian

Christian:

Thanks for the kind words along with your thoughtful comments and questions. Clearly, you are thinking deeply about these issues.

1) Shortening the test to 30 minutes makes sense to me and should still give you a good AeT HR. Smart move!

2)If you are training on flat ground pace is a better metric than HR. So, yes, using pace will be better for you.

3)I’ve never used drift the way you suggest. I think doing so might be false precision. Besides, AeT HR or pace will change depending on recovery status. Try using nose breathing as a limit for AeT for a few days and see if it correlates well to your AeT pace.

4)I have seen negative HR drift but it always comes from finishing with a down hill. I’ve not seen this sort of negative drift. Sorry

Scott

Scott, thanks so much for sharing these revised thoughts. Previously, I had been blindly adhering to HR zones, as my understanding from your previous writings was that monitoring nose breathing was only really accurate for the most aerobically well-trained athletes and so I was too inexperienced for it to be accurate. Since reading this and combining nose breathing monitoring with HR monitoring, I’ve been able to improve my Z1 running economy by not slowing down as much when my HR drifts into Z2; previously, I would’ve blindly adhered to my zones and avoided this like the plague even if this drift into a Z2 HR still felt like an easier Z1 effort. I’ve also begun to increase the duration of my longer runs because I’m no longer as worried about my HR drifting into Z2 over the course of longer. 60 min+ runs as long as nose breathing still feels very comfortable and the perceived effort still feels like Z1. Looking forward to many more of these articles from Evoke!

Andrew: Thanks for the comment. Yes, the combo of using a ventilatory marker like nose breathing with a HR monitor will give you better results than relying hard and fast on the data alone. After more time you will begin to use your perception of effort as the best guide to intensity. The HR monitor becomes just a check. From what you are saying, I would suggest you re-evaluate/re-test your aerobic threshold. It sounds like your AeT HR and pace have moved up.

Scott

Scott, apologies for the late reply. I don’t think there are email notifications for replies to comments; if there are, I haven’t figured out how to turn them on.

You’re spot on about my AeT; I’m due a re-test this week. I had been focussing on running at a Z1 level of effort because I was finding that Z2 runs were starting to become a bit too taxing on the body to repeat day in/day out, even though the aerobic effort was still at or below AeT. If I remember correctly, when your Z2 pace becomes too fast and taxing to repeat day after day, that’s a good sign that your AeT is with 10% of your AnT. Admittedly, I’m also due an AnT re-test.

Andrew:

The more aerobic capacity you build, the faster you will be able to run in your aerobic zone. Running at the aerobic threshold for fit runners can be quite fast. IN those cases the neuromuscular load becomes too high to do a very high volume at this intensity and more Z1 needs to be used. Sounds to me like you’ve done a good job on your training.

Scott

All thanks to a couple of excellent books and their generous authors!

I am having a hard time finding the right heart rate despite a lot of testing and retesting. I’ve done this test a few times now. I seem to settle in around 129 bmp and I get virtually no drift. I am also tracking the heart rate across two devices to ensure there isn’t some sort of error. The wrist shows heart rate of 130, chest 129. I am tempted to just add around 6 BMP to the very clearly low level (129) for my threshold and call it good for now. I am a touch sick of the retesting and simply can’t bring myself to do it again. Or should I go with 129-130?

Thanks, this article lays it out very clearly.

I don’t have a training peaks account but I do use a HRM.

Is it possible to do a drift test by recording two sessions during a treadmill test? After warming up and finding my starting heart rate I can start one session, then after 30 minutes stop that one and start a second session. Then compare the average HR from one session to the other.

Thanks and kind regards

Ryan

Ryan:

Yes, that will work if you have a way of finding the average HR for each section of the test.

Scott

Scott,

If you use Garmin gadgets, you do not need a Training Peaks premium account to calculate average HR for different time intervals.

In Garmin Connect app on Android (I assume that it works the same on iOS) you can:

– Select an HR graph under activity

– rotate your smartphone horizontally

– zoom on a particular time interval of your HR graph using two fingers

– select start of time interval with one finger and end of time interval with another finger:

Garmin Connect will display an average HR for this time interval

Yury

Yury:

You can do this in Garmin Connect like you mentioned.

Scott

Cam:

When we see a zero drift test, and we don’t want to have to do yet another test we do exactly what you are thinking: add about 5% and train using that as the top of Z2. Keep in mind that the AeT will vary from day to day based on recovery status. If 135 feels hard on a certain day, then don’t push the pace just to hit 135. listen to how your body is reacting to the training stress you are applying. When 135 begins to feel easy and you notice you are moving at a faster pace at that HR, consider redoing the test then at 140.

Scott

Thanks!

Thanks Scott

Yes I have just done one. I stopped my first recording at 30 minutes and immediately started a new recording which lasted another half hour. Comparing the average HR from the two has given me a drift of ~3% so I’ll do another one in a couple of days at a slightly higher HR but it seems alright for a first try.

Ryan

Hi Scott,

i would almost like to use phrase “Thank you for your service!” to express my gratitude for your work on fitness for mountain athletes. TfTNA changed my life for the better – not only with new gained fitness, but the discipline and structure it brought to my life – and i had some of my best alpine climbing experiences after following training for a half-year cycle for the first time. Again, thanks a lot for your work. It is much appreciated – and unfortunately hard to promote among fellow alpinists from Slovenia…

In my second cycle i decided to determine my AeT with HR drift test, after inital 6 weeks of transition and 8 weeks of base. I have two or three questions:

1) Both tests were done on treadmill. In the first one, i did 10 min warmup, followed immediately by 60 minutes run at 6kmh and 10% incline. First half of the workout (warmup excluded) had avg. HR 143, and second had 144. When i repeated test next week (12min warmup, 60min run, 7,2kmh, 10%incl.) i got a drift from 155 in the 1. half to 159 in the 2. half – that is 2.5%. Is that worth repeating at higher intensity to score between 3.5 – 5%, or can i set AeT based on this test? The test are tiring and i do not like treadmill 🙂

2) I did both tests with mouth breathing, but i do all my Z1 (currently 120 to 140 bpm) training with nose breathing. Are you supposed to nose breathe while testing?

3) Also, while i train for alpine climbing and mountaineering, i do a lot of training running. Are my settings (10% incl.) OK, or would you change something?

Thanks a lot for any answers you might give. I almost cannot believe you do that for free 🙂

I wish you (and the rest of the team) all the best in new year!

Peter

Peter:

Thanks for your kind words. The reason I and all the coaches left Uphill Athlete and formed Evoke is that we are passionate about sharing our knowledge and helping people.

Based on what you have said I think you can use the second test and call the top of Z2 at 159. If running at this pace on 10% incline felt hard you should consider doing an Anaerobic Threshold test. I’ll bet that you AnT is not more than 10% above 159. If that is the case you probably don’t want to do much training in the top of Z2.

It is not necessary to breathe through your nose but it is a worthwhile practice to learn so you don’t need to rely on the HR monitor all the time. You listen to your body more.

I hope this helps.

Scott

Curious about how long it takes for people to typically regress out of the 10% AeT/AnT after a layoff? Do atheletes need to retest and regain their good AeT each season?

@Aaholmes

Sadly, aerobic capacity is probably the slowest quality to accumulate and the fastest to go away. That’s because the most important changes are structural and mean having to grow new protein structures like capillaries. However, the structural changes are there for the long haul. What does diminish quickly with cessation of training are aerobic enzymes and mitochondrial density. These come back in a matter of days to a few weeks once you resume consistent training at a volume similar to your previous load. One study showed that 5 days of bed rest reduced mitochondrial density by 50%. When you begin to train again, you will want to concentrate on Z1-2 work to restore that lost aerobic capacity. You’ll feel pretty unfit, but within a couple of weeks, you will probably be back to feeling decent again. Don’t bother retesting till you’ve got 4 -6 weeks of base training back under you.

I hope this helps.

Scott

I think this article help me connect some dots I was not quite getting (after studying both your books and all the content on Uphill Athlete before Evoke came to be!). Does this sound right?

It sounds like first you build your aerobic base to address ADS and lift the AeT to within 10% of AnT, I get that. But then you later in Z3 and Z4 work for performance which lifts AnT HR for performance peak.

After the peak, you then go back to building the aerobic base again, lifting AeT back to within 10% of your NEW AnT. Thus the cycle continues until you reach some physiological maximum determined by your physiology and genetics?

Thanks again for all you do!

Hey Scott,

Avid cyclist, and sport climber…but I haven’t run in years, except to catch the bus. I tried to do a Z1 run the other day, but got all sorts of sharp pains in my feet and ankles I didn’t know I had (since I hike, climb, bike, walk with no pain), and I’m only 32.

I’m just not running for right now, walking fast, walking stairs, biking. And I’m gonna try to do some strengthening of my tibialis, as my calves are already plenty strong I think.

But do you know any way to get a good AeT without running? Or can I use my nose breathing, TP 60minute recent average from cycling to get a rough idea of where my AeT is?

Best,

Jared

Jared:

Great questions. This might sound nutty, but you need to find your AeT for each training modality you will be using. Running and hiking uphill are usually pretty close, but running (or hiking) and biking are probably not close to each other. The reason for this is that you are having to support your body weight while foot borne, and you are sitting on the bike. Much less muscle mass is involved in cycling.

As for the pain in your feet and ankles: You are too young to have such issues unless you have serious structural deformities. I suggest beginning a very slow jogging program where you jog for 2 min and walk for two minutes. The impact loading, even in slow jogging, is about 2x body weight at each foot strike. It takes many thousands of

Jared:

Great questions. This might sound nutty, but you need to find your AeT for each training modality you will be using. Running and hiking uphill are usually pretty close, but running (or hiking) and biking are probably not close to each other. The reason for this is that you are having to support your body weight while foot borne, and you are sitting on the bike. Much less muscle mass is involved in cycling. You can effectivel y build aerobic capacioty hiking, although being young and healthy you will probably need to be hiking uphill to get your heart rate high enough.

As for the pain in your feet and ankles: You are too young to have such issues unless you have serious structural deformities. I suggest beginning a very slow jogging program where you jog for 2 min and walk for two minutes. The impact loading, even in slow jogging, is about 2x body weight at each foot strike. It takes many thousands of impacts to strengthen the connective tissues (tendons, fascia and ligaments) in your feet and legs to the point they can handle running.l ramping up running distance too fast is the main reason people get lower leg injuries the stop them from being able to run. As a species we were made to run. If you can’t run it is indicating some deeper problems. Jusy be slow and gradual. We help a lot of people return to running using this run/walk program. As you progress with it you can increase jogging time.

I hope this helps.

Scott

Scott,

Thanks so much for the in depth answer. Not too nutty at all! Based on what you wrote in TFNA I figured I’d have to figure out each modality’s HR zones.

Gonna work that out this week. I have the biking set. So I’ll use my HR strap and phone and these flights of stairs I have, 25m up and down, to do a HR drift test.

And I think I’ll swap one stairs workout each week for a walk run program as you suggested.

When I was a teenager I destroyed my ankles playing football (soccer), and they never properly recovered, because I didn’t let them, so I suspect that has something to do with it. But, like rock climbing and needing to give tendons and ligaments more time to handle the load than the muscles, I will keep this in mind for my feet and running.

The odd thing is, if I sprint, I get no pain. I think it’s because my sprinting form is halfway decent and I’m not impacting the ground really strongly, it’s that fluid midfoot strike, but my gait or something seems harsher when I’m going slower.

But perhaps it’s just the structural strength, we shall see how things go over the next few weeks. Got Switzerland and some multi-pitch sport climbing at the beginning of August.

I know I have it deep inside me, the ability to run, my body remembers I’m sure, I was a good athlete back in high school, ran a 17min 5k. Ran a half-marathon just for fun once, so I know I can go distance. Used to hike all day in the Cascades and then still climb multipitch routes. So hopefully the my neurological system can help the body remember how to get in shape for all that again.

Jared:

I hope you can find a way to run again pain-free. Your feet and ankles are an incredibly complex structure of 26 bones, 29 muscles, and all the interconnective fascia, tendons, and ligaments. All of these respond to training if your approach is gradual and progressive. Good luck with that.

I’m not sure that doing laps on 25m stairs will yield a good result for a HR drift test. It might I’ve just never done it that way. Hiking on a treadmill set to 15% is going to give you a good test, as will using a stair machine. But these two tests are likely to give different results because the steeper stairs (or machine) is significantly more a test of muscular endurance than hiking up an incline. If most of your hiking is on trails between 0% and 15% grade (typical forest trails in the Cascades), you should try to define your AeT on a treadmill set to 10-15%.

Hey Scott, roger that. I will pay the day entrance to a gym then and do it on the treadmill at 15%.

Unfortunately, I live in London now, so stairs are the best I can get, cause I’m not near any of the few big hills here. I do have the surrey hills about an hour and a half bus ride away, or about an hour bike ride away. There’s a steep long hill there I’m hoping to use for ME workouts later on.

Jared,

I used stairs for training and conducted a simplified version of this test hiking just two flights of stairs (~7 m of elevation gain) repeatedly up and down.

Although my HR was not absolutely steady, I feel that such periodic variance was small enough to correctly use such exercise for this test.

Yury

Hello Scott.

I was trying my indoor AeT on treadmill today. I though of HR 120 as my base, but even with 15 minutes warmup I had to setup quite a speed to keep the rate there so I though 110 may be more realistic to hold for 1 hour. Incline was 15% and speed 4km/h. I tested for some minutes and HR was stable at 110.

Restarted the test to have full one hour. For the first 15 minutes HR as around 110, the it gradually went to 120 (peaking at 125), strange thing happened around 45 minutes when the HR started to drop and dropped to minimum of 95BMP before returning to 110. I have not changed any settings on the machine and was trying to keep the pace same. Now I’m really puzzled and unsure what should I take from this result.

Could you please help me out?

Thank you

Zed

Zed:

I have never seen a result like this. The rise in HR followed by a drop down to 95 and 110 could mean that 110 was too low a HR to start with. The only thing I can suggest is to try again. I wish I could give more and better advice.

Scott

Do these benchmarks hold for cyclists? I have a LT1 of 220W @ 130bpm, and a LT2 of 350W at 162bpm. I train about 15-20 hours a week almost exclusively zone 2 and have accumulated over 600 hours of training for the last 3 years, but these figures reflect a ~20% bpm difference and suggests my LT1 is still quite weak (which I’m very excited about if it means I have a lot of improvement I can still make).

How do I increase my LT1 further, and what role does HR decoupling play in training LT1?

Ben: Yes, these are markers that represent significant metabolic events that occur across all endurance sports. The higher the Lt1 and closer to LT2, the bigger the base and the more endurance-specific work you can do to improve performance. If you have not retested LT1 recently, that’s a place to start. It may be that your LT 1 has increased. HR decoupling is the same as HR drift. Any decoupling between HR and pace or power less than 5%/hour indicates you are at or below LT1.

Scott

Hi Scott,

Thanks a lot for the article. I am 29 years old and training for mountaineering. After a few attempts to find my aerobic threshold, It looks like it is somewhere around 147bpm (4.6% drift). I now try training close to 147bmp. The problem I am finding is that my heart rate tends to vary a lot. One minute I am at 135bpm, the next i am at 150bpm. Even with a steady pace on the threadmill. I am using a chest strap monitor (polar h10) which is supposed to be precise. I am not sure if such variability is ok and how to train without having to adapt the pace every minute to stay close to 147. I am used to hiking a lot and have done sports my whole life. Could you please advise me how to approach this issue?

Thanks,

Denis

Denis:

A jumpy HR is not unusual, especially if you are new to, say, running and do not have your technique dialed. HR is a response to the muscle work being done. When you see those lower HRs, you might take note of how the effort feels different than when you see HR spikes. Careful and sensitive observations can help you “feel” when you are moving with a better economy.

That aside, though, try not to spend much more than about 10% of your aerobic base training volume above your AeT. Going above it now and then for a few seconds is not a big deal and is unavoidable if you are trying to stay close to 147. You just don’t want to spend 50% of the workout above AeT or you end up with a different training effect than the one you are trying to target.

Hi, I did the HR Drift Test, but unfortunately the drift was only 1%. i Started it at 151BPM, but got high very early, reaching 156-160BPM and stabilizing there for the rest of the run. Next day, I went for a basic run, and did 60min, all nose breathing. It went from 139-150 in first tenn minutes, and then in last 50min going somewhere in between 150-160BPM, averaging 154-155. I am starting my new designed training program next week and little injured, so have no time to redo test. Is it reasonable to put my AeT at 154? (my previous spiroergometry tested was 151BPM half a year ago, trained a lot since).

Thanks!

Jakub:

Based on this information of a very low drift of one percent and being able to nose breathe for 50 minutes up to 160 bpm I would say that you would be very safe to put your AET at 1:54 and probably even as high as 160 on the days when you feel good.

Scott

I appreciate your article. I’m not sure if you’ll see this, but hoping you do.

I did your test 3 times on the treadmill bumping it up each time. My last test was with a 2% incline at 5.0mph. I nose breathed the entire time. My HR was 165 and didn’t drift. I have a Polar H10 so I think my test was accurate.

This result feels really high to me. Especially since I haven’t trained very consistently in the last few months.

Is there any explanation for these type of results?

Dave:

If you did this test 3 times with that same result then I think you are doing the test right. Do you have previous data from earlier tests? Or even from previous training runs? Heart rates are highly individual and 165 might be the max HR for one person and Z1-2 for another who has a max HR of 210. In the same way, resting HRs can run from the mid-30s to the 80s. There is no such thing as a ‘correct’ HR.

What was your perceived exertion? That can be valuable information.

It seems to me that based on the zero drift and the nose breathing you might want to redo the test at a faster speed.

Scott

Thank you, Scott. I don’t have any previous test data to compare to as I just recently found your site and content. The perceived effort was fairly low. It felt like an easy run. I could have gone for another hour, which makes me think that I was in Z2 but that I’m also probably aerobically deficient. Since my drift test, I’ve continued running outside and have focused on nose breathing to help moderate my pace and HR. My HR gets up to the mid 160s and stays there over the course of my 1 hour long runs. My pace is around the 11:00 mark and is fairly consistent depending on the trail I’m running.

I plan to do another drift test here in a couple weeks. In the meantime, I’m going to continue to nose breath on my runs and build my aerobic base. After some time (months maybe), would it be reasonable to expect my HR to stay somewhat consistent around the mid 160s while my pace gets faster?

Dave:

Depending on things like the volume of Z2 running, your age and your genetics your AeT will noticeably improve on the time scale of 4-6 weeks to a couple of months. Initially, both pace and HR will increase. Eventually, the AeT HR can’t go any higher and plateaus. However, we have seen the AeT pace continue to improve for several years.

Scott

I did the test for the MAF-Plan starting in block one I aimed for 149 while it stabilized the drift was just about 1%. So I guesstimate a rate of 152? If so, is this a good way to structure the other zones or do I ignore the other ones for now, because I´ll be focussing on Z2 anyway? Z1:114-133,

Z2:133-152, Z3:152-171, Z4:171-190, Z5:190-209

TK: Your calcs for Z1 and Z2 seem fine based on the drift test. I can’t say about the other zones. I suggest reading this article. I think it will help you set those upper zones most effectively. https://evokeendurance.com/setting-your-hear-rate-zones/

Scott

Quick question about the HR Drift Test. I’ve read that heat and dehydration can also increase drift, so is it okay to drink water during the test or will that invalidate the results?

Brief background: AeT of 138 and AnT of 160 and I’ve been training exclusively in Z2 for the past year (5-8 hours per week) with no improvement in my AeT. Every time I conduct the drift test on a treadmill with 15% incline with a HR higher than 138 to start, things go fine for the first 45-50 minutes of the test and then my HR jumps 10-12 bpm for the last 10-15 minutes of the test which skews the second half average HR higher so my spread is always >5% (usually in the 7-9% range). I’m theorizing that dehydration at the very end of the test may be driving the HR up, but haven’t tested this theory yet.

Risto:

Do you notice an increase in your perceived exertion (RPE) in those last 15 minutes? What is your overall RPE in the middle of this test? It could be that your AeT and AnT are close enough together that going at about 140HR at 10% is actually “hard”.

I take it that you have not seen any improvement in your pace-to-HR ratio in normal aerobic workouts. The improvement we typically see happens when one day you are running the same loop you train on regularly and you notice: “Hmm, I’m 3 minutes faster to that landmark than I was 2 months ago. This does not mean that every run will see such an improvement but when looking at the trend you will see a positive trend.

If you are using Training Peaks you can look at the Analyze button and check the Pa:Hr ratio for your aerobic workouts and see if there is a trend. This only works with GPS so not indoors.

I hope this is some help.

Scott

Hey Scott,

Thanks for the advice! I definitely notice an increase in RPE during the last 15 minutes; it feels more like an anaerobic threshold test than a drift test. RPE in the middle of the test feels comfortable hard. I can still nose breathe comfortably, but the physical effort feels higher than “go all day” easy. Maybe I need to add more muscular endurance training to allow muscles to keep up with the aerobic system?

All my workouts are done indoors on an incline treadmill set to 15%. I have noticed that my pace-to-HR ratio seems to have increased. I have to set the treadmill speed higher at the start of the workout to get my HR up to my AeT and finish my workouts with a higher speed than months ago (I decrease the speed through the workout to keep HR below AeT).

Is it possible that I’ve reached my genetically predetermined max AeT? I’ve seen so many posts from folks with AeT >150 that I assumed mine should go above 138 at some point (I’m 48 with some aerobic conditioning background from hiking and cycling, but no formal training experience). Would this mean I don’t have ADS even though the spread between my AeT and AnT is still >10%?

Thanks!

Risto:

The comments about RPE tell the story for you. If training at what you feel (and from your comments I agree) is your AeT feels muscularly hard you need to respect that and not try to train at that intensity every day. I would include 1x/week of ME work, either weighted hiking under a very heavy load or the Gym ME program. I would also add in 1x/week of Z3 intervals on the 15% incline. Im guessing a bit here but you might want to start with a heart rate around 145-150 and start with a total of 30min of hard work in this session. That could be every thing from 2min on 1 min easy all the way to 2x15min with 2-3min easy between. If this intensity is too hard to allow you to recover in 2 days drop the HR you use for these. I think you will see improved endurance in 2-3 weeks. Don’t worry that your HR is different than other people. That is completely irrelevant.

Good luck.

Scott