Evoke Endurance Athlete Female Physiology Basics

By: Kylee Toth

Posted:

While mountains and mountain pursuits have long been the domain of men there is a long and storied history of women climbers going back to the infancy of the sport of climbing mountains in the middle of the 19th century. These ladies had to overcome huge hurdles and not just the scorn of the men; imagine climbing in a floor length dress! One hundred years later the hurdles still remained. The first summit of Everest was done by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay in 1953 while the first female summit wouldn’t come until over 20 years later by Junko Tabei in 1975. While women have engaged in mountain pursuits for centuries, it has taken them time to gain a seat at the proverbial table and we are still striving to make headway in 2022.

The same can be true for female training and physiology. The vast body of research into human performance and training science has been conducted on men. While there are fewer studies done on women, the last 40 years has seen an increase in frequency and number. It is exciting to see the nuances of female training, methodology and physiology being recognized.

At Evoke Endurance we have many female coaches and train a plethora of female athletes for the full spectrum of mountain sports. Evoke recognizes the need for inclusivity, respect and high performance training for the female mountain athlete and alpinist. This article touches on the main points surrounding female athlete physiology; strength, speed, power, aerobic and anaerobic energy systems, mobility, agility, technique, hormones and the mind. The article is not intended to be a comprehensive look at female physiology. Hopefully, it will point out some differences between the genders, considerations for female mountain athletes and serve as a launching pad to connect with formalised training. Every female is unique, keep this in mind while you read all the science and information provided. It is your body, your plan, your choices and your life.

Firstly, for both men and women, strength is largely a neurologic quality that depends on the brain’s ability to recruit the greatest number of fibres for a task. The simplest definition of strength training is performing exercise by applying resistance against which the muscles need to exert force. For both female and male mountain athletes strength training is used to improve performance and for injury prevention, not to become stronger in the gym.

For many years women were hesitant to strength train largely due to a fear of looking like a bodybuilder. Fortunately, that myth has largely been dispelled, and it is now commonly accepted that women can get strong without getting huge. It is a myth, however, that females can’t put on any muscle mass with weight training. Look at speed skaters, weight lifters or swimmers and you will see a sport specific body type. The same could be true for mountain athletes. Many female climbers have well developed shoulder and back muscles. However, that type of muscle development takes a great deal of training, dedication and years of combined strength and sport specific muscular endurance training.

Women’s lean muscle mass is distributed differently than men’s. Women in general have stronger lower bodies compared to their upper bodies. Women tend to store fat around the hips and thighs, whereas men are prone to storing fat around the stomach. “In-vitro adipose tissue biopsy data has shown that women display differences in lipolytic activity between upper body and lower body adipose tissue compared to men.”1 Female power comes from hips and legs. Women carry more fat than men. Essential fat in women represents between 10-13% of body weight, whereas in men it represents only 2-5%. The reason for this difference is that women have to stock energy in the form of fat in anticipation of future pregnancies (and must stock even more energy during the last two trimesters of pregnancy). This is primarily why female muscles can look less defined, and the elusive six pack is harder to achieve.

In general, males have larger musculature. Ever struggle to do a chin up while the guys beside you hammer out dozens? This may be due to females in general being less strong than males in the upper body primarily due to muscle size. The good news is female muscles are as trainable as men’s. With proper training women can be very strong.

Both male and female muscles are made up of type 1 (aerobic/slow twitch fibres) and type II (anaerobic/fast twitch fibres). Generally, men have larger type II fibres than women. This makes putting on muscle and producing more power easier. Another key factor in muscle development is testosterone levels which are significantly lower in women.

So, now that we have set a foundation of differences between male and female strength, why is strength training important for mountain athletes? And what are a few things we can do to be the best female mountain athletes we can be?

Why is strength training important for female mountain athletes? Strength training is really important under the age of 30 for maximum bone density and strength. Over the age of 30 it is important to retain strength as we age. Starting at age 35, women lose muscle mass at a rate of 1-2% per year, and this increases to 3% per year after age 60. Also, they don’t shrink and pink mountain packs for alpinism; mountain athletes need to efficiently carry gear, food and supplies. For the endurance mountain athlete, strength training helps create lean muscle mass and aids in injury prevention.

What can we do to be the best female mountain athletes we can be from a strength perspective? As the stereotypical gym rats like to say, “don’t skip leg day.” All kidding aside, placing emphasis on sport specific strength after a period of general strength is a principle of Evoke Endurance training. Exploring a max strength cycle will help build strength without bulk for climbing or alpinism. If you are wanting to improve at mountaineering, ski mountaineering or a repetitive discipline that requires a very good strength to weight ratio, a prescribed muscular endurance program is advisable.

For women, body image often plays into fears around strength training and even perception of ability. Understanding your somatotype may help you set realistic body image goals and embrace what you have been dealt genetically. There are three main somatotypes: endomorphs, ectomorphs, mesomorphs. It is important to note that athletes and mountain athletes are found in all three somatotypes. Endomorphs are generally persons with a soft, round build and a higher proportion of fat tissue. Ectomorphs are characterised by a linear thin, more delicate body with small bone and muscle structure and mass. This body type has the tendency to look more defined and conventionally “athletic.” Lastly, mesomorphs are a classification between ectomorph and endomorph. Mesomorphs have some muscle tone as well as fat. Perhaps female mountain athletes need to take a more utilitarian approach. By thinking of their body as a high performance machine, rather than an object of aesthetics, may help. Asking yourself what prescribed training do I need to do in order to reach my goals, rather than how will this make my body look? Another consideration for females is the role hormones play in building muscle strength. This will be discussed later in this article under the heading Hormonal Health and the Endocrine System.

Want to be able to dyno better for that next hold? Boulder at a different level? Have cat-like reflexes when you ski your next pillow line or jump turn like a Chamonix steep skier? Perhaps speed and power needs to become your super power. The definition of speed is the rate at which someone is able to move. Speed is a valuable tool in the mountains for both performance and safety. Have you ever tried to dodge a tree on skis? How about getting off a summit before a storm closes in? Set an FKT on a local peak? If you have, you will know having fast reflexes and good neuromuscular connections combined with a monster aerobic base is pivotal to being a dynamic mountain athlete. Speed and power go hand in hand.

Let’s get into the science. Core samples of muscles taken from men and women show we have similar numbers of fast twitch (type II) fibres and slow twitch (type 1) fibres. The difference between men and women lies in the size. Men’s type II fibres are generally larger. This explains why men, at the highest level, still dominate women at anaerobic pursuits such as weight lifting, sprinting, etc. There is a commonly held myth that being lighter will always make you faster. Not necessarily; you can get faster by working on power and technique. Strong, responsive legs can provide a more powerful foot strike or rebound when running. Strong, powerful arms can drive an ice axe with less effort and more precision.

So, what are a few things we can do to be the best female mountain athletes we can be using speed and power? For the mountain athlete, strength training helps to build speed and power. Your type II fibres are engaged through heavy lifting. Building neuromuscular connections through strength and agility training that is sport specific will help too. As endurance athletes, we place a heavy emphasis on aerobic training. Aerobic training produces a better metabolic turnover, increases your ATP (energy) available which makes muscles more powerful and equals more speed. Female brains are wired to multi- task better than our male counterparts which may make us better at building neural pathways for speed and agility.

In the genre of speed and power, it’s important to note that fastest known times (FKT’s) aren’t just for men. FKT’s for mountain peaks are something that both men and women aspire to achieve. While these efforts lasting a long amount of time are primarily done in your aerobic zone, sprinkling in some neuromuscular activities to help with agility and the neural connections needed for speed will help to be lighter on your feet, less prone to injury and more agile. It would be awesome to see more women tackle FKT’s. Speed and power when combined with a solid aerobic base may be an important ingredient for success.

If you have ever been bouldering you will inevitably see someone bring their foot above their head, moving in a gymnast fashion. How about watching a graceful skimo racer run up a slope or an extremely efficient ultra runner dance through a boulder field. The ability to move easily and with maximum efficiency would be the simplest definition of mobility, as it pertains to mountain athletics.

One of the fundamental differences between men and women when it comes to agility and technique is our body structure. Women in general tend to be wider at the hips than men and have a larger Q-Angle. The Q-Angle is a measurement of the angle between the quadriceps muscles and the patella tendon. This leads to women often being more knock kneed or pronated. Women in general are also more susceptible to knee injuries than men for this reason. A startling statistic is that women are 3 to 6 times more likely than men to have injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). No need to worry though; these limitations can be mitigated with proper strength training and technical work. It is imperative for women to strengthen their glutes, quads and hamstrings. Women also have a less stable shoulder joint with looser supporting tissue and weaker shoulder muscles. This makes training for exercises that involve the upper body (pull ups, chinups, lock offs, and some climbing specific moves) more challenging and more prone to injury than for men. The good news is, with awareness and training we can make great gains in these areas. But, it is important to progress smartly and slowly, building up the proper strength to prevent injury.

Female hormones that undulate through the month such as relaxin, progesterone and estrogen also may give women a mobility advantage over men. Our connective tissue is slightly more lax. This can be advantageous for sports that require flexibility like climbing.

Both men and women can become great technicians. What women lack in raw power and strength can often be improved upon. They can have more power with good technique. For many recreational mountain athletes, technique is an often overlooked component. In ice climbing for example, many women do not have as much force to drive the axe as their male counterparts do, but with proper technique they could out climb their partner. The same can be said for rock climbing. For females trying to get the edge on the competition or to improve on their personal best, look at practising more efficient movement patterns.

Mobility and getting to your end range or full range of motion can help you get gains in rock climbing, ice climbing and mixed climbing. Even in endurance disciplines, fluid movement and full range can be mechanical advantages. If you are looking to improve training your aerobic system, improving your strength to weight ratio and becoming a technician are all key ingredients in the tool box. On a practical side yoga for recovery and injury prevention could be a great tool to improve your mobility and build neurological (mind-body) connective pathways to help you improve technique.

The key to mountain athletics lies in the metabolic pathways, the energy you use to move up mountains. For both females and males, understanding your aerobic and anaerobic system is pivotal to becoming a finely trained machine. Aerobic is, simply, in the presence of oxygen. This means your heart rate is lower and your body is getting adequate oxygen to sustain output and create energy. Anaerobic means without oxygen. This encompasses that feeling of not being able to push anymore, high heart rate and effort. If you want to be a lean, mean, female mountain climbing machine, you better get your house built on a firm foundation of aerobic activity.

An anaerobic activity is defined as energy expenditure that uses anaerobic metabolism (the use of carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen) that lasts less than 90 seconds, using a maximal effort. Two major energy sources fuel this effort. Firstly, the adenosine triphosphate-phosphocreatine (ATP-PCr) system lasts for 3 to 15 seconds at a max effort. The second system is anaerobic glycolysis, which can be sustained for the remainder of the all-out effort. To our knowledge, anaerobic metabolism happens the same in both males and females. If you are interested in this system in depth, read chapter 2 in Training for the Uphill Athlete.

The second metabolic pathway to produce ATP (energy) is our aerobic system. This is a complex, multistep chemical process which occurs inside the muscle cell’s mitochondria and requires oxygen in order to function. Aerobic metabolism produces roughly seventeen times more ATP than the anaerobic path, but is a more complex and hence a slower process. The basics of our aerobic metabolic pathway are the same in male and females. Please refer to Chapter 2 in Training for the Uphill Athlete if you are interested in learning more about this.

For the purpose of this article, we want to point out considerations and differences for the female athlete and thus will focus on those. Females in general have a smaller engine, meaning the actual size of our hearts are smaller. Think F150 versus Honda Civic. The heart muscle is also slightly weaker. We have lower diastolic pressure (pressure in the arteries when the heart is resting between beats and the ventricles fill with blood). Our lungs also have 20-30% less capacity than men’s, due to females being smaller in general. Females also have lower testosterone than men. Testosterone increases red blood cell production, which absorbs and carries oxygen to working muscles. Men on average have 6% more red blood cells and 10-15% more hemoglobin (which is the molecule in red blood cells that carries oxygen to muscles). All of these structural and muscular differences make women, on average, have lower maximum heart rates. Smaller lungs and lower maximal heart rate gives us lower VO2 max (maximal volume of oxygen that can be used). The top recorded males VO2 is around 90, while the top recorded female VO2 is under 80. With smaller lungs and less oxygen, our respiratory systems need to work harder than a man’s at high intensity.

While our “engine” is generally all around smaller, there are some interesting nuances that might explain why females are still relatively close to males at certain sports. Some research supports evidence that during low intensity efforts women oxidize more fat, less carbohydrates and less amino acids compared to men.2 Women may have inherited ketogenic responses to exercise.3 One hypothesised reason women are excelling in longer endurance sports is they are naturally more fat adapted. Women also generally have larger type I fibres than type II fibres, which may contribute to their success in long endurance feats. One rock climbing study showed that while female muscle fibres were less powerful, they fatigue less quickly than their male counterparts.4

A study of men and women at altitude showed that women actually have a lower reduction of VO2 max at altitude.5 This shouldn’t be misinterpreted as we are better than men at high altitude, as we start from a lower VO2 max to begin with. It does show that women are, and will continue to be strong partners and players in high altitude mountaineering.

On the anaerobic side of things, having slightly smaller muscles than our male counterparts and smaller type II fibres, we produce slightly less lactic acid on average. This could be an advantage at your local race when the overbuilt gym guy next to you charges out of the gate, but after 15 seconds explodes with lactic acid and you go running briskly by.

After reading all this you may feel like women don’t stand a chance against men. While the gap in performance between men and women remains, and will probably continue that way in sports where anaerobic metabolism plays a significant role (those events lasting less than 90 seconds), the gap in endurance sports, especially those lasting many hours, is not so large. However, your focus should be on becoming the best version of you that you can possibly be.

We can’t change our physiology, but we can train it. This is why we see many females “chicking” men in races. The mean gender gap in most disciplines of sport (at a high level), is about 10%. Most data has been calculated using sports like Track and Field, Swimming and Speed Skating. I thought for the purpose of this article it would be interesting to look at mountain sports. In the chart below I have compared the top female times or grades to the top male times or grades to find the percentage of difference. The point of this is not to say women aren’t as good, or to diminish them in any way, but to look at the differences to see where our strengths and weaknesses lie. I do think we will see some women close the gender gap, but it will take ingenuity, intelligence and mental fortitude to achieve this. In fully understanding female differences and physiology, women can train differently and work to their advantages. By continually training like, “little men,” women will not achieve their full athletic potential as female mountain athletes.

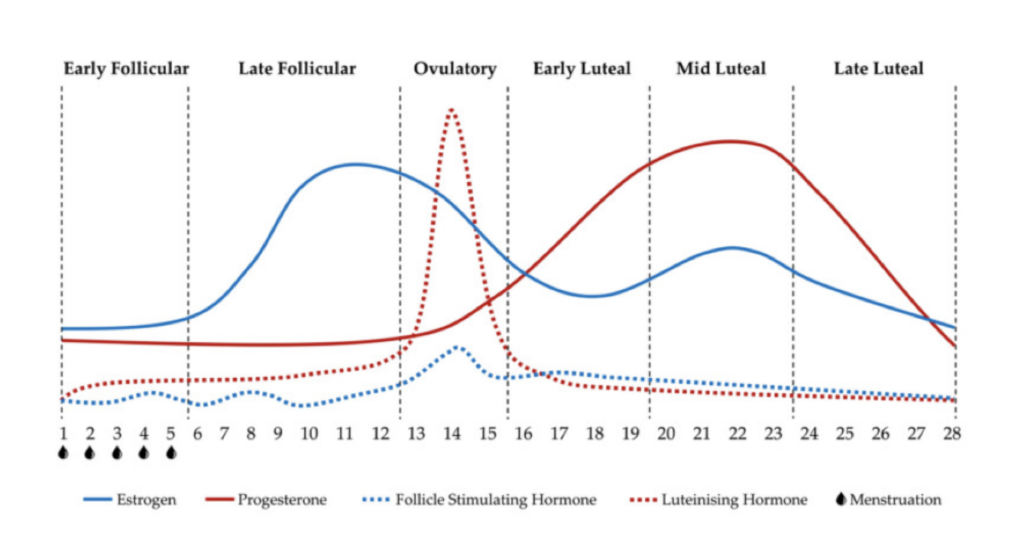

Perhaps one of the least talked about and most misunderstood areas of a female athlete’s physiology is their hormones. It has long been understood and widely accepted that men and women have differing levels of hormones. The male athlete’s dominant hormone is testosterone. Men’s testosterone levels can be as much as 15 times higher than women’s, so it is no wonder that men on average tend to be bigger and stronger. Testosterone increases during adolescence and stays fairly constant until age 40, when a slight decline begins. Females, on the other hand, get a mountainous profile when it comes to the fluctuation of estrogen, progesterone and other less dominant hormones that fluctuate in our body each month as part of the reproductive cycle. The range of “normal,” for the length of a female menstruation cycle is anywhere from 28 to 31 days. The interplay of female hormones on energy and mood should be of interest to all mountain minded female athletes.

Physical performance has been postulated to change over the course of a menstrual cycle due to various mechanisms such as altered muscle activation, substrate metabolism, thermoregulation and body composition. Female sex hormone concentrations could be responsible for altered force production. This may affect muscle strength and power. Estrogen has a neuroexcitatory effect and progesterone inhibits cortical excitability. These neuroexcitatory and inhibitory effects result in estrogen and progesterone possessing a positive and negative relationship with force production, respectively.6 Progesterone is known to have a catabolic effect when it comes to strength production. For athletes looking to increase power, this should be taken into consideration when it is peaking.

Women who participate in endurance sports may miss periods or stop menstruating. Almost every female I know has either experienced this or known someone who has. While common in the female athletic world, this is not necessarily healthy, especially in adolescents who are developing proper bone density. This is called secondary amenorrhea, and it occurs because the ovaries are not producing enough estrogen. It is believed that stress and low body fat contribute to amenorrhea. Further research has shown that even women with adequate body fat can experience loss of periods. It has been postulated that inadequate or disordered fueling, even in females with healthy body weights, could lead to this as their bodies are sent into a state of stress which causes hormone regulation problems and signals the body to conserve and protect. Female athletes may use many harmful strategies, including excessive dieting, excessive exercise, irregular or inadequate fueling, bingeing, and purging, in order to lose or maintain weight. On the extreme end, the female athlete triad is a combination of three conditions that are common with athletic training: eating disorders, such as bulimia or anorexia; the absence of menstrual periods (amenorrhea); and osteoporosis. It is said that a woman’s fat percentage, whether high or low, as well as their weight and cortisol levels, are reasons for amenorrhea. The bottom line is, if a female athlete is continually missing periods this should be a sign for further investigation with a physician, and should not be accepted as normal.

Fasted exercise is another tool used in athletic training that has conflicting results for women. Fasting can send women’s hormones into chaos because of our need to protect our fat stores for procreation. Women are more sensitive to intermittent fasting than men because they have more kisspeptin, which is associated with reproductive functions and creates a greater sensitivity to fasting. Women are also more sensitive to cortisol, which increases during fasting. Cortisol is a stress hormone that has desirable fat-burning properties, but that may also cause hormonal imbalances for women. Fasting can improve insulin sensitivity and increase metabolism. Contrary to continuous calorie restriction, fasting will not make you feel hungrier in the long run. Instead, it increases leptin and adiponectin levels, which improves the feeling of satiety. Moreover, it affects the hunger hormone ghrelin and improves dopamine levels (the happy hormone). Fasting for women has not been shown to be universally good or bad, but it is important to be aware of what could be happening on an endocrine level if it doesn’t work for you.

In order for female athletes to fully understand their hormones, understanding the three phases of the menstrual cycle is pivotal. Each phase is further broken down into sub-phases but it is not necessary to overcomplicate things for a good basic understanding. Perhaps one of the reasons the menstrual cycle hasn’t been taken into consideration or applied in female training programs is its complexity and nuances from person to person. The menstrual cycle can last 28-31 days on average for women. The chart below is a basic diagram of how female hormones fluctuate throughout this period. Generally people refer to “day one” as the first day of bleeding, and count from there. It should be noted that although studies have shown there are certain athletic advantages and disadvantages at different stages of the cycle, world record performances and personal bests have been set at all stages.

Figure 1

Hormonal events and phases in a eumenorrheic 28-day menstrual cycle. Adapted from McNulty et al. 7 and Farage et al.8

The first day of a period marks the beginning of a new menstrual cycle. During a period, blood and tissue from the uterus exit the body through the vagina. Estrogen and progesterone levels are very low at this point, and this can often cause irritability and mood changes.

As this phase continues, the pituitary gland releases FSH and LH, which increase estrogen levels and signal follicle growth in the ovaries. Each follicle contains one egg. After a few days, one dominant follicle will emerge in each ovary. The ovaries will absorb the remaining follicles.

As the dominant follicle continues growing, it will produce more estrogen. This increase in estrogen stimulates the release of endorphins that raise energy levels and improve mood. Estrogen also enriches the endometrium, which is the lining of the uterus.

As mentioned earlier, estrogen rises and peaks during the later stages of this phase. Estrogen strengthens the effect of insulin (the hormone that causes storage of carbohydrates and synthesis of new proteins), meaning carbs are better tolerated and muscle is more easily built at this stage. 9 Some studies have shown that strength training in the follicular phase is more effective because of lower levels of progesterone. Progesterone causes a thermogenic (heat generating) response through a rise in metabolic rate, which would increase catabolism10 Some research has found that strength training during the follicular phase resulted in higher increases in muscle strength compared to training in the luteal phase because of lower levels of progesterone.

Hormone levels, metabolism, and energy levels begin to balance out again during menstruation as the body prepares itself to begin another cycle. Female athletes might find this to be a good time to reset and evaluate their training programme, reflecting upon the variations in strength, energy levels and motivation throughout the previous cycle.

Another athletic consideration in the follicular phase when estrogen is high has to do with mobility. A recent meta-review of studies looked at how hormonal changes may impact tendon laxity and risk of tendon injury. It found the risk was highest in the days leading up to ovulation, when estrogen is high.11

Mood is likely to be positive throughout the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, which lasts approximately 16 days. During this time, both estrogen and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels increase. The increased levels of estrogen in the body can potentially mitigate the effects that hormones like cortisol, the stress hormone, and adrenaline can have. This can help to maintain a happier mood. Many athletes have reported feeling best in this first half of the cycle.

During the ovulatory phase, estrogen and LH levels in the body peak, causing a follicle to burst and release its egg from the ovary.

During the ovulation phase of your menstrual cycle, pregnancy is possible. The ovaries release a mature egg into the fallopian tube to get fertilized by a sperm, and estrogen levels are high. The high levels of estrogen can influence other hormones such as insulin, which promotes the action of testosterone and can increase libido (sex drive). Another hormone, called luteinizing hormone (LH), is also increasing during the ovulation phase of the menstrual cycle.

There is very little specific research on athletic performance during ovulation. However, it marks approximately the middle of the cycle, and is a significant marker in the shift of hormone production to progesterone, which occurs in the next phase of the cycle.

During the luteal phase, the egg travels from the ovary to the uterus via the fallopian tube. The ruptured follicle releases progesterone, which thickens the uterine lining, preparing it to receive a fertilized egg. Once the egg reaches the end of the fallopian tube, it attaches to the uterine wall.

An unfertilized egg will cause estrogen and progesterone levels to decline. This marks the beginning of the premenstrual week. This rapid decline in hormones is often attributed to premenstrual symptoms such as cramping, low mood, increased appetite, etc.

Finally, the unfertilized egg and the uterine lining will leave the body, marking the end of the current menstrual cycle and the beginning of the next.

Based on the info above, some athletic females have found success with scheduling rest days during the late luteal phase. In order to figure out ovulation baselines, taking ovulation tests for a few cycles can be helpful. Ovulation can shift cycle-to-cycle, but it’s usually your follicular phase that’s getting shorter or longer.

Also, in order to reduce impact on your strength goals, the luteal phase is the best time to take time off from training for vacation. In the luteal phase, progesterone rises significantly. Body temperature is also higher during this phase — body temperature shoots up by at least 0.4 degrees celsius after ovulation and stays high until menstruation.12 The late luteal phase (3-5 days before the start of the period) is the phase that aerobic athletes have often felt at their worst. This is often attributed to the rise in body temperature and crash of both progesterone and estrogen. As a result of rises in body temperature during the luteal phase, metabolic output may increase by as much as 90-280 kcals per day! This is why women often feel cravings right before their period starts. However, studies have shown that many athletes and records have been broken during this phase. To say women are “impaired” aerobically at this time is most likely untrue.13 For some women, knowing why they are feeling a certain way helps them to mitigate or plan to avoid symptoms. All this said, it’s important to take the above as a rough guide only. There are studies which suggest that there is no significant impact of menstrual cycle on athletic performance in the general population14 and others that point to declines.

Toward the end of this phase the production of progesterone is maximized before drastically falling (along with levels of estrogen). It is this sudden change in hormonal levels that is thought to underlie premenstrual syndrome (PMS), causing symptoms such as depression, fatigue, anxiety, headaches, cravings, water retention, and an increase in core body temperature. This may explain why, during this period, many people lack motivation, feel mood changes and find exercise more taxing than usual.

For the female mountain athlete, having an awareness of what is happening in her body may help her to understand why she is feeling a certain way. The annoying adage that, “females are just more emotional” or “women are roller coasters of emotion,” may not be so ambiguous and puzzling.

It would be nice if there was a one size fits all prescription for females managing their periods, but as is the nature with all physical training, each person is unique. The one thing that all female mountain athletes can start doing is tracking their period, and I don’t mean writing a little star on the calendar when it starts. What I mean is using a sheet (like the one below) or some other journal method that details how she feels in the four phases. Early follicular phase (during her period), late follicular phase (after the period stops for approximately 7 more days), early luteal phase (the 7 days after ovulation), and late luteal phase (premenstrual time, 5-7 days before the next period begins). By understanding what is happening in her own body, the female athlete can make appropriate changes to her training and eating schedules. Many women have found the use of supplements or even pharmaceuticals such as aspirin helpful at different times of their cycles. Sometimes even simple changes like focusing more on hydration, intaking a few more calories or taking an extra rest day, can go a long way. For many females just the understanding of what is happening hormonally can explain a lot of emotions and can help performance. Knowledge as to “why” you feel a certain way can be powerful.

Technique and ability alone do not get you to the top; it is the willpower that is most important.

Junko Tabei of Japan

This extraordinary woman was the first woman to summit Everest and ascend the Seven Summits, climbing the highest peak on every continent. Perhaps one of the strongest features of the female mountain athlete is her mind and her propensity for mental resilience. Strength of mind and willpower has been shown on countless occasions to defy logic and training in many ways.

Many studies, done primarily in the business world or that relate to addiction, have shown that men are more adventurous and risk taking than women.15 Whether this is an innate trait that is hardwired into them, as part of our hunter- gatherer origins, more culture driven, or personality related, is yet to be determined. However, it is widely accepted that women are biologically designed for reproduction and self preservation. Our hormonal cycles, musculature, bone structure and how we store body fat all are congruent with this reproductive design.

While it has been postulated that more mountaineering feats have been accomplished by men because of a propensity for less self preservation, especially in adolescence and early 20s, there are many factors that play into the predominantly male culture. Socioeconomic factors in a historically patriarchal society, gender norms related to activities that are socially acceptable or that males versus females are permitted to participate in. It is also a product of basic math; there are more men than women engaging in most mountain sports.

The important point here is to realize that, yes, women have been underrepresented in this arena, but are no less capable mentally. In fact, many females have extremely high risk tolerances that have developed through methodological exposure to risk over time, and in many ways are less careless or reckless than our male counterparts.

Additionally, there have been reported sex differences of the nervous system responses in catecholamines during endurance exercise and high stress situations (such as epinephrine, norepinephrine and dopamine). These central nervous system differences affect stress levels, preferred use of fuel and mood during exercise, and may be a key difference between sexes.16

Females in general have a high pain tolerance and propensity for suffering, which in alpinism and mountaineering can be a very good trait. The process of carrying a child and giving birth is part of the female design. Anyone who has experienced this, or born witness to this process, can attest to it being a monumental feat of human strength and resilience. To say women are the “weaker” sex is fallible from so many angles.

Just as the athlete trains the body, the mind too can be trained. Self control, risk tolerance, how you react under pressure and high stress, are all things that can be improved with exposure, practice and mental exercises. Many female olympians, mountaineers, climbers, endurance athletes and alpinists have exceptional stories of mental fortitude and strength overcoming seemingly insurmountable obstacles and limitations physically, environmentally and mentally. Like the training of the physical traits we’ve talked about, mental training takes consistency and a gradually increasing training stimulus.

“Sex differences are sexy, but this false impression that there is such a thing as a ‘male brain’ and a ‘female brain’ has had wide impact on how we treat boys and girls, men and women,” Dr. Eliot said in reporting on her massive meta-synthesis study of three decades of research.

“The truth is that there are no universal, species-wide brain features that differ between the sexes. Rather, the brain is like other organs, such as the heart and kidneys, which are similar enough to be transplanted between women and men quite successfully.”

This is an exciting time to be a female athlete. We are becoming more aware of the similarities and differences between the sexes and more research is going into female-specific training. As I conclude this article, the point that I wish to emphasize is that our race is not to catch the men; our race is to see what women are capable of as our own unique species and entity. Female athletes need to have a strong understanding of the fundamentals of training. Curiosity and thinking outside the box in order to work with our uniquenesses in physiology will help female mountain athletes find the methodology that works best for them. I encourage all female athletes to understand their bodies, be proud to be female, and work extremely hard to be the best version of themselves they can be. Evoke Endurance prides itself on science-based and ingenuitive thinking, so circle back here often to learn more about female physiology as it relates to mountain sports. If any of the topics in this article have sparked your interest, delve deeper with free resources on the Evoke Endurance site. You will find many articles and podcasts by the Evoke Endurance team coming soon. If you want to join a community or have a specific goal in mind, check out our female specific training groups or get custom coaching to suit your needs.

1 Blaak, E., Gender differences in fat metabolism. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 2001. 4(6): p. 499-502.

2 Tarnopolsky, M.A., Sex differences in exercise metabolism and the role of 17-beta estradiol. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2008. 40(4): p. 648-54.

3 Davis, S.N., et al., Effects of gender on neuroendocrine and metabolic counterregulatory responses to exercise in normal man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2000. 85(1): p. 224-30.

4 Rylands, L. P., Cheetham, M. A., Crawford, A., & Taylor, N. (2018). Power Performance Characteristics in Male versus Female Sport Climbers: A Lab Based Study Using an SRM Power Meter. Journal of Exercise Physiology Online, 21(5).

5 Bhaumik, G., Dass, D., Lama, H., & Chauhan, S. K. S. (2008). Maximum exercise responses of men and women mountaineering trainees on induction to high altitude (4350 m) by trekking. Wilderness & environmental medicine, 19(3), 151-156.

6 Carmichael, M. A., Thomson, R. L., Moran, L. J., & Wycherley, T. P. (2021). The Impact of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Athletes’ Performance: A Narrative Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(4), 1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041667

7 McNulty K.L., Elliott-Sale K.J., Dolan E., Swinton P.A., Ansdell P., Goodall S., Thomas K., Hicks K.M. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01319-3.

8 Farage M., Neill S., Maclean A. Copy of Physiological Changes During Menstruation. [(accessed on 9 February 2021)];2012 Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 257239400_Physiological_changes_during_menstruation.

9 D’eon, T. and Braun, B., 2002. The roles of estrogen and progesterone in regulating carbohydrate and fat utilization at rest and during exercise. Journal of women’s health & gender-based medicine, 11(3), pp.225-237.

10 Kalkhoff RK. Metabolic effects of progesterone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982 Mar 15;142(6 Pt 2):735-8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)32480-2. PMID: 7039319.

11 Herzberg SD, Motu’apuaka ML, Lambert W, Fu R, Brady J, Guise JM. The effect of menstrual cycle and contraceptives on ACL injuries and laxity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. 2017 Jul 19;5(7):2325967117718781.

12 Herzberg SD, Motu’apuaka ML, Lambert W, Fu R, Brady J, Guise JM. The effect of menstrual cycle and contraceptives on ACL injuries and laxity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. 2017 Jul 19;5(7):2325967117718781.

13 Carmichael, M. A., Thomson, R. L., Moran, L. J., & Wycherley, T. P. (2021). The Impact of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Athletes’ Performance: A Narrative Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(4), 1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041667

14 Constantini, N.W., Dubnov, G. and Lebrun, C.M., 2005. The menstrual cycle and sport performance. Clinics in sports medicine, 24(2), pp.e51-e82

15 Jing, Chen. Gender Differences in Risk Taking: Are Women more Risk Averse? University Van Tilberg. Link: arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=81419

16 Zouhal, H., et al., Catecholamines and the effects of exercise, training and gender. Sports Med, 2008. 38(5): p. 401-23