Training for Rock Climbing: A movement-first Approach to Training

By: Dave Thompson

Posted:

Note From Evoke: An edited version of this article appears under another author’s name on another website. However, Evoke Endurance coach Dave Thompson, the author of this article, is the originator of these ideas and wrote the original of the other site’s article.

Training for rock climbing is complex. After all, rock climbing has unique demands for strength, power and endurance while at the same time being a highly technique-dependent sport. Couple those

demands with the fear/risk component makes training for rock climbing particularly challenging. In this article, we intend to discuss training for rock climbing by breaking it into its fundamental components and examining each of those separately.

Despite the complexity, effective training for rock climbing must still follow traditional sports training methodologies:

As well, the following overarching training principles:

All these combine to allow you to train sustainably and achieve high-level performances while staying injury-free.

Because technical skills and strength are the dominant requirements for climbing on the rock, the same heart rate zones that are so useful in endurance sports are impractical and not useful for moderating intensity. That said, what rock climbing training does share with training for other mountain sports is that a consistent training volume and a broad and reliable base of skills and abilities are necessary for progress.

We’re going to start by helping you form a mental model of how effective rock climbing training is. Models are useful when they simplify complex systems so that they are more comprehensible. To do this, we need to oversimplify reality, breaking it down into more digestible concepts.

As mentioned above, the overarching training principles must be incorporated into the optimal mixture of skills, endurance, and strength, which support efficient, safe, and reliable climbing movement. Whether you are training for a big wall free climb or a three-move boulder problem, both activities require the same foundational elements.

For any movement of the body to take place, a cascade of events must occur, originating in the nervous system and ending in the muscles. Voluntary movements, from walking to executing a one-arm pull-up, require various levels of excitation of the nervous system and musculature to be performed.

To illustrate this, let’s take the act of walking as our first example. While complex, walking is a well-conditioned neuro-muscular action for most of us, and because of the sheer repetition of millions of steps, the nervous system and the associated musculature involved in taking a step are conditioned to perform this action very reliably. Walking is ‘easy’ because the signal given by the nervous system to the muscles is so robust that all that is required is a relatively low-level signal from the nervous system for this action to take place.

This is because the signal is carried efficiently and reliably through long-term adaptations such as myelination, which insulates nerve fibers allowing for the signal from the nerves to be carried with a high degree of efficiency to the associated musculature. Thus, the various systems of the body that contribute to the act of walking require a very low threshold of excitation between the nervous system and muscles of the lower body. An infant struggling to walk is an extreme but excellent example of this stage of motor pattern learning.

Let’s contrast walking with what is a far less conditioned movement for most people, the one-arm pull-up. The primary reason a one-arm pull-up is not as easy as walking (which is a more complex movement involving balance) for most people is that the nervous signal and associated muscles have a much higher threshold of excitation for the muscles to produce this act. The signal from the nervous system to the core, shoulder, and arm must be of much greater input to innervate the necessary muscle fibers to produce the movement.

From basic studies in muscle physiology it is observed that fast-twitch fibers are the last in succession to contribute to a muscle contraction because of their higher threshold of excitation. However, something that is not often emphasized is that both slow-twitch and fast-twitch muscle fibers are trainable to have a lower threshold of excitation. This is precisely why a movement like a one-arm pull-up can go from impossible to easy over time, and also how you learned to walk in the first place.

So, how can you direct this process to produce consistent performance gains? More importantly, how do you determine where to intervene to train reliable increases in skill and performance?

The first foundational quality of training for rock climbing is the accumulation of a high volume of climbing-specific movement skills.

Skill acquisition sessions must be done when you are well-rested for the intensity of the climbing you wish to perform. Do this training early in the workout before you get fatigued because the first physical quality to deteriorate with fatigue is fine motor skills. Climbing combines coarse (a simple movement like pull-ups) and fine (like moving through a tricky, tenuous position) motor skills. The combination of fine motor skills and strength separates the best from the rest.

In order to improve, you’ll want to know how robustly a specific skill holds up under duress, whether it be a max-strength movement such as a one-arm pull-up or the precise core stability required to dance up a sustained, foot-intensive face climb.

You will need to increase your awareness: Consider how your internal state aids or hinders your performance. Think about the simple skill of walking and talking at the same time. This is an instinctual skill. In contrast, have you ever noticed how people stop talking when they get to the crux of the climb? They have to focus deliberately on the moves required to pull through. Cultivating this observer state is the foundation for identifying our personal strengths and weaknesses. Your weaknesses encompass your edge abilities. Edge abilities are defined by your failure to perform them or by a sequence of moves or a climbing style that feels subjectively ‘weird’ to perform.

Remember, you are training to lower the threshold of excitation of the muscles involved in climbing movement so those movements can be performed with more frequency, reliability, and fine motor control. Performance gains occur over time only if you determine the skills you lack and train them so that they are integrated into your instinctual vocabulary of movements. The steps in this process are outlined below in the stages of conscious habit formation.

Stage 1) Unconsciously unskilled: you have low skill in some areas and low awareness of this lack of skill. You don’t know what you don’t know. Think of the baby learning to walk.

Stage 2) Consciously unskilled: You have low skills but are aware of this and consciously work to acquire good skills. You know what you don’t know.

Stage 3) Consciously skilled: you have high(er) skills but must work consciously to apply and improve them. You actively work to learn what you would like to know.

Stage 4) Unconsciously skilled: you have high skills and do not need to think about them any longer because they are ingrained. This is the stage of mastery.

‘Mastery’, however, is a slippery fish. It is a fleeting and emergent result of consistent work in the first three stages listed above that precipitates out of first identifying what you don’t know and then actively working to learn what you would like to know.

To illustrate this process, let us break down these stages when projecting a rock climb that is at the edge of your ability, starting from the beginning and culminating in a red point.

You have your eye on a specific route. Perhaps you’ve seen a video of someone climbing on it, conversed with a fellow climber who has attempted the route, or even red-pointed it yourself. You have a vague idea of the sequences but zero personal experience on the route. Basically, you know a bit of second-hand information about the route, but from a purely experiential perspective, you don’t know what you don’t know.

Your first attempts on a route provide an essential litmus test that informs your subsequent encounters with it. In this initial stage of attempts, some basic questions to keep at the front of your mind are: do you have the physical capacities that meet the demands of the route? How narrowly can you define your present physical capacities as they apply to the demands of the route? Questions like these shine a light upon potential approaches you have available to address deficiencies in strength, power, endurance, movement vocabulary, stability, and mobility. Here is where adopting the observer mindset becomes important. This initiates the process of beginning to know what you don’t know.

This is the stage where the acts of practice and training superimpose themselves upon the specific demands of your project route. There is no upper or lower end regarding the time this stage requires. Practice it wrong and you get really good at doing it wrong. Further, the first two stages remain essential parts at every step of the way. You are aware and working on improving these qualities.

The more finely you can practice and train for the demands of your goal route, the quicker your active learning will inform what you need to know and guide your approach. For instance, perhaps your goal route has sections of moves that you struggle to perform even in isolation. Here, it behooves you to investigate alternative hand and foot sequences on the external landscape of the route and the potential myriad ways you could alter the sequencing, recruitment, tension, and relaxation of your individual muscles internally. It is important to note that the more robust your internal sense of your body’s interaction with the external surface of the rock, the clearer your perception will be of the methods at your disposal.

To explore this further, say, for instance, while attempting the route, your foot slips repeatedly on a sloping foothold in a delicate section of the climb. Going through an iterative process, starting from the contact you make with the rock and working to more central joints and body orientations, helps you better understand the subtle shifts necessary for proper execution.

For instance: Are you using the best area of the foothold? Does dropping your heel give better quality contact with the hold? Are your hips oriented such that you are optimally applying as much force as possible, but not too much, to the hold? Are you able to make small adjustments in the muscles of your core to allow you to balance and apply force? – This is all to say that you likely have many more options than you may have initially realized, and it is your task to find them and determine what works.

Both Narrow and Broad: This is the stage where the body itself learns and internalizes the movement and where the iterative process above yields successful actions that shift awareness from finer to broader levels of attention.

Continuing with our example above of climbing through a sequence that requires fine-scale force distribution on a sloping slippery foothold: If you adopt the observer state, you will notice over repeated successful attempts that your body orients itself into the proper positioning of all of the joints of the body in an increasing degree of absence of your awareness of the fine scale adjustments you initially determined were required for successful execution of the sequence. This is because your body has learned and mastered the movement. Thus, you are now executing unconscious skills.

This same process can be applied to more broad aspects of a route’s physical requirements as well. For instance, you are told that your goal route has a twenty-move section in which there is no opportunity to rest (Stage 1). You verify that, yes, it is indeed the case that you must perform a twenty-move sequence, and this is at the edge of your current capacity of power endurance (Stage 2). You train your body to execute sequences of similar movement number and difficulty and also refine your movement execution on the route itself over multiple attempts (Stage 3). Over these repeated attempts, you are then gradually able to execute this twenty-move sequence with more efficiency, thus decreasing levels of fatigue (Stage 4).

It is important to note that these stages seldom align with a particular period in the training cycle, but they can help you assess your training and skill development to understand your specific edge abilities to which a training cycle can be dedicated.

The important thing is that you learn what it is that you have to do to move from Stage One (Unconsciously Unskilled), to Stage Four (Unconsciously Skilled), and do that over-and-over again into perpetuity. If you practice a move repeatedly wrong, you will simply get better at doing it wrong. This is because the instinctive mind doesn’t distinguish between ‘right’ and ‘wrong.’ The observant climber will replace inefficient movement patterns that he or she is accustomed to with those that are more efficient while striving for perfection.

When you have identified specific skills that require conditioning and practice, there are multiple regimes to choose from that can aid greater levels of robustness along the full range of low- to high-intensity levels of climbing.

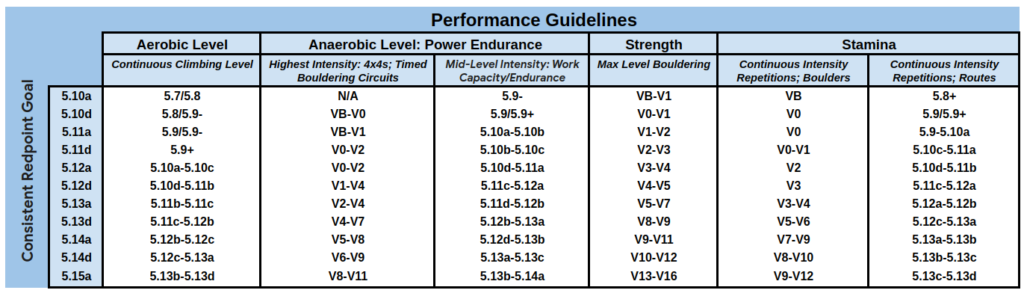

For the purposes of illustration, we’d like to include the following table adapted from the book, The Self-Coached Climber.

From the book: “These general guidelines are consistent with solid performances such as on-sights, or fast red-points, as well as with continued improvement to the next level. They do not represent the minimum requirements necessary to climb a specific grade.” Said differently, if you want to be consistent in climbing at a particular grade, these performance guidelines can be used to assess your own abilities and train specific areas of deficiency.

Your continuous climbing level, power endurance, strength, and stamina must be trained up to the maximum demands of your goal routes. There are several areas of general conditioning that must be tailored to this process while training for rock climbing. You’re trying to take movements and known vertical distances that are currently at your limit and make them into movements and volumes of climbing you can do repeatedly. Keep in mind that endurance is not limited to multi-hour efforts. If one month ago you could only do 1 repetition of a particular movement, and now you can reliably do 5 reps, your endurance has increased greatly.

For an athlete with a short aerobic training history, this can take the form of aerobic base training through increasing metabolic efficiency by working on general fitness through running, hiking, cycling, cross-country skiing, and other longer-duration efforts. While it won’t directly impact your climbing ability, improving basic aerobic capacity with the activities mentioned below in the ‘Aerobic Base’ section will improve your overall work capacity and shorten recovery times both within a training session and between training sessions.

For novice and beginner climbers, general fitness gained through non-climbing activities like running or lifting weights can drastically improve body composition and general strength, but these non-sport specific activities on their own will not make you better on a rock once your aerobic base and general strength are sufficient To progress from there, you will need to add structured climbing-specific training, addressing deficits in specific skills, strength, and endurance.

Here are two examples that will illustrate the spectrum that an individual climber may present with and then highlight how they may approach their own key limiters while training for rock climbing.

Has a long history of rock climbing on many different types of rock. They have climbed at a relatively consistent grade for many years but have plateaued and are looking to increase their ability.

The path forward here is to identify the key limiters that are contributing to the plateau and to train more efficient solutions when confronting ‘edge abilities’. Add in easier, higher volume climbing, focusing awareness of the movement patterns that support these edge abilities. Couple this with activation training of specific muscle groups off the wall that can be incorporated into harder sections of moves and higher-volume climbing. A spray wall, Treadwall, mirror image board (such as a Tension Board or a Grasshopper Board), or Moonboard are great climbing surfaces to help identify your individual key limiters.

They are relatively new to climbing but have enjoyed some highlights and successes that have made them want to understand what it will take to consistently increase their level of climbing.

Being relatively new to training for rock climbing, it is important to establish habits of movement that will be essential for higher grades. This is done by increasing strength and work capacity in functional movements and emphasizing skill acquisition during all climbing activities. Perfect practice makes perfect execution.

The main difference between these two examples is: Climber #2 is learning and applying new skills, Climber #1 must unlearn and replace the old, less effective ways of moving on rock, which is actually harder than learning new skills for the first time.

Keep in mind that movement-based training is the foundation of reliable movement patterns. New skills must be trained both in isolation and in concert with more robust and well-developed skills. Base movements and skills run the spectrum from one-repetition maximum strength, such as max dead-hangs, to long-duration climbing intervals where a specific skill is trained during the act of climbing. These two ends of the spectrum, as well as regimes that fall in between, are outlined below. These various training regimes can be tailored to the specific situation of each climber.

As we have said many times, a well functioning aerobic system allows the body to work at a high efficiency, as well as to recover both during training and between training days. For the activity of rock climbing, Zone 1 and Zone 2 runs and hikes support and maintain an efficient aerobic system. This non-sport-specific type of aerobic base training will be especially useful if you have even moderately long (30 min or longer) approaches. For information on aerobic base training, see:

(AKA “ARCing”): Long-duration or high-volume climbing provides a number of beneficial structural and metabolic adaptations. Whether in local muscles such as the forearms or systemically in terms of whole-body work capacity, long-duration intervals are a fantastic time to condition connective tissues, gain general endurance, and drill robust skills and movement patterns. Continuous climbing times lasting from several minutes to a half hour or more are best for achieving the proper training effect.

Some guidelines for finding the proper intensity level for this activity: The ability to maintain a low level but continuous pump in the forearms; the ability to stop and self-correct faulty movement patterns; the ability to stop and rest on the climbing surface to properly manage pump and fatigue to fulfill the predetermined duration of climbing time. This is best performed on an auto-belay, a bouldering wall, or a Treadwall. See our article on Treadwall Training.

These are intervals of climbing times between three to seven minutes or so. They are best tailored to the difficulty of the non-crux sections of the climber’s goal routes but these times are only a rough guideline. For instance, if your goal route is a multi-pitch 5.13 with a V6 boulder crux interspersed with 5.11+/12- sections, you would benefit greatly from the ability to climb the non-crux sections and pitches while only accumulating a mild to moderate level of fatigue. You should focus on the ability to make moves in the aforementioned state of intensity such that you can successfully navigate this terrain in a mildly to moderately fatigued state.

Start with climbing-to-rest intervals that start at a 1:3 ratio. Doing this consistently with a gradual progression over the weeks and months will allow you to decrease this ratio to 1:1, increase the work capacity (more work done in less time), and move the climber to a higher level of endurance. When the climber is able to climb for a longer duration without needing to rest, the level of climbing used in the Continuous Climbing or ARCing sessions will be elevated as well.

You can assess your stamina levels by answering the question: What particular route or boulder grade can you do a lot of in a single session? This is climbing at a continuous level of difficulty without getting a pump. This can be performed outdoors or in the gym. On routes, this can be done by climbing 10-15 pitches while aiming to not get a forearm pump. On boulder problems, do 15-30 problems. For either routes or boulders, aim to rest a sufficient amount of time such that you are carrying minimal fatigue into subsequent routes/problems. Fatigue will inevitably accumulate and will be perceived as a ‘powered down’ feeling in the working muscles but with little to no residual pump.

Climbing intensities at levels encountered at the cruxes of specific projects form the basis for the climber’s power endurance training. Several approaches can be used to improve the climber’s ability to climb reliably and efficiently in crux terrain.

Outlined below are several examples of ways to target power endurance. The goal here is to make your power endurance training progress in ways specific to the demands of your goal routes. The key is to be powered down at the end, but only going right to the point of hands opening and core sagging out and ending the workout there. Time rests such that you are able to get through your chosen circuit, and reduce these rest times by 15-30 seconds based on this over subsequent sessions. Try to increase the number of rounds that you accumulate over subsequent climbing sessions while using the level of ‘power-down’ mentioned above as a guide of when to stop this session.

Remember: Respect the Power-Down

The key is to be powered down at the end, but only to the point of hands opening and core sagging out, and ending the workout there.

Doing a circuit of boulder problems that includes attempts and/or completion of three or four different climbs that are at or slightly above crux difficulty, along with easier climbs that are gradually increased in difficulty up to that found on the non-crux terrain of your project. This is best implemented by first training your project-level difficulty boulder problems in isolation with enough rest time in between that you are able to complete each. Track your rest times between each completion and reduce your rest times by tuning in to the moment you are ready to give a successful attempt. Gradually fill rest times with climbing that is easy enough to allow you to still complete the original climbs. This can be done by adding this easier climbing immediately after the completion of the original problem that reduces total rest time between each crux level boulder problem.

Emphasize increasing the difficulty and moving the number of these easier problems to the same level as is found between crux sections of your project climb and further reducing the rest time such that you can climb the entire circuit continuously without resting on the ground. Aiming for 3-5 boulder problems at the crux level of your goal climbs with 1-3 easier problems in between will provide a robust training stimulus.

Pick four boulder problems that are around your flash level, and involve 5 to 15 moves. Preferably pick problems you have done in the past, with an emphasis on physical moves and no inconsistent beta. Err on the easy side in workout #1 if you’re unsure of how hard the problems should be. Move between problems quickly. Rest for two minutes after the four problems. Repeat three more times.

Pick a climb a grade or so below your flash level. Climb the route and note the time it took you to complete it. Rest an equal amount of time as the climbing time. Repeat this four to seven times. End the workout when technique suffers. This is a less specific routine than that given above in the training outlined in the ‘Bouldering Circuits’ section, but works well for general preparation.

A more advanced version of this is best used as a means of increasing the work/rest ratio to that found on your project routes. For instance, if you know that a project requires you to be climbing continuously for three minutes between rest positions, and you can recover at rest for a maximum of two minutes, simulating this work/rest time while training will condition you for your project. You can start by resting off of the wall for the allotted rest time and, over subsequent sessions, gradually transition to resting on the wall for the entire rest period.

There are many specific strength and power exercises that lead to gains in climbing ability. However, just because these are easy to measure and see progress, gains in these areas are only part of a well-rounded training program for rock climbing. For strength and power training, a “less is more” approach trains specific weaknesses and deficits and allows the climber to apply the gains acquired through this training directly to the climbing movement. Rather than outline specific training regimens in detail, we will highlight the training benefits and give a brief example routine.

Proper limit bouldering involves climbing sequences of moves at max, or near-max, difficulty. Sequences can be as little as one or two moves but must be right on the edge of a climber’s ability. Limit moves are tried many times during a session with ample rest time and personal reflection on how to improve the movement quality for the next attempt. There is no upper limit on rest times between attempts, but a minimum of two minutes is usually sufficient.

A proper limit boulder problem can require many sessions to complete and many more to perfect. Because of the difficult nature of the individual moves, it is important to discontinue the session when movement quality degrades. This means, over the course of a session, if you reliably get to move five of a limit problem but then find yourself unable to execute move four, stop the session, or move on to a different problem. To continue to unsuccessfully attempt to limit moves to the point of exhaustion causes the body to learn the movements improperly and will actually make success less likely in subsequent sessions on the same problem.

Pick six boulder problems at or above your current limit. Choose problems of varying angles that target your weaknesses. Aim for a success rate of 30% to 70% in problem completion. Attempt problem one for six minutes, which should be roughly 3 tries. Focus on max effort and quality attempts. Rest for 6 minutes, and repeat this for all six problems. If you complete a problem on the first try, remove that problem from your next session, and add a new problem.

*Author Dave Thompson doing Limit Bouldering on “One Move Wonder,” an 8A/V11 on the Moonboard

Campusing is climbing without the use of the feet and legs. It is a useful exercise for improvement in dynamic, powerful movements. The rapid and strenuous nature of campusing places high demands on a large muscle mass, causing the nervous system to be maximally recruited. This can be beneficial for training the body to generate speedy movements in an efficient manner. A proper campus training session is structured similarly to a limit-bouldering session, where attempts at maximal efforts are separated by long (>3min) rest times, and quality is emphasized over quantity.

Workout Progression: As you begin to plateau (i.e., get the same PR in two consecutive workouts), drop down to the medium-sized rungs. Do two workouts at this rung size, aiming to equal your PR on the larger rungs. After the two workouts on the medium rungs, go back to the large rungs, aiming to beat your previous PR.

Because climbing performance benefits from a high strength-to-weight ratio, a focus on relative strength as opposed to absolute strength elicits more climbing-specific strength and power. Training on gymnastic rings, or some variation of a suspension trainer, a pull-up bar, and a box, often suffices to prepare the climber for the rigors of climbing movement. A high-level general strength and power routine on these apparatuses would include Front Lever, Front lever pull-ups, Pistol Squats, Single-Leg Box Jumps, Muscle Ups, arm pulls, Planche, and the Iron Cross. Each of the movements listed can be done in less intense variations by using assistance or increasing mechanical advantage. There are countless videos on the internet that demonstrate methods for less intense variations of these movements.

Keep in mind that it is not necessary to be able to do all of these movements in their purest forms, but this set of movements covers the vast majority of strength requirements found on rock. Thus, while training for rock climbing, a climber who performs easier variations of each movement while striving towards doing them in their purest forms over a protracted period of years and decades will benefit greatly from the performance increases they elicit on the way.

As rock climbing requires pulling the body up the wall, a climber can benefit from a variety of pulling exercises. Pull-ups are the most obvious example of exercises that translate well to rock climbing. But simply doing hundreds of pull-ups a day will do little to increase climbing ability and can lead to overuse injuries in the elbows and shoulders. A better method is to do weighted pull-ups or one-arm pull-ups in low rep ranges. Usually, doing this once or twice a week, along with other climbing-specific training, is sufficient to increase strength and keep the climber’s elbows and shoulders healthy.

Pull-ups are the king of upper-body exercises. While climbers can debate the applicability of pull-ups to hard climbing, there is no doubt that they’re great for general strength training. They involve almost all of the body’s muscle groups from the waist up.

For our purposes, we define ‘the core’ as everything that is not arms, legs, and head. A solid and durable core is the foundation of all strength, endurance, and athletic ability. Training the core for the demands placed on it by rock climbing involves general core stability while the climber rotates, extends, contracts, or resists rotation. Training for rock climbing should involve challenging core stability in a variety of positions and orientations. Simply doing crunches may give you a six-pack, but does little to address the specific demands put on your core during climbing, or any other athletic activity for that matter. For an example of a good general core routine that is a staple here at Evoke Endurance, check out Scott’s Killer Core Routine.

In short, hang boarding improves finger, hand, and forearm strength and, when done properly, is excellent for injury prevention. Keep in mind that strengthening the structures of the hand is a very slow process. Because of this, consistent loading over weeks, months, years, and decades accumulate to make the hand capable of sustaining very high loads. There are a million-and-one hang board routines out there, but most fall into three basic categories: maximum hangs, repeaters, and long-duration hangs.

Almost every day, do five to ten hangs of around 8-10 seconds, with plenty of rest in between each hang. Work up to about 80% of your maximum hang time for a given edge size or other type of hold. This can be performed as one-armed or two-armed hangs, depending on your strength level and the specific types and sizes of holds you are targeting. Auto Regulation Primer: There is a degree of autoregulation intended in this workout. Your ability to hang on a particular edge for a particular time will vary from day to day and workout to workout. The important thing is to do quality hangs that are ~80% of the max. That may be on a larger edge or a smaller edge on any given day. Just know that it is the consistent loading of the hands over weeks, months, and years that makes the foundation of strong hands.

These involve hanging from the smallest or poorest hold that a climber is capable of for periods of ten seconds or less. Often weight is added to the body to manage this time period. As a guideline, once a climber can hang a particular hold with around 133% of their body weight, they should use a smaller hold.

Here is an example of a max hang routine: Complete a pyramid of six 6-second hangs separated by 2.5-minute rests. The first hang should feel easy, and you should barely complete or fail on the final hang while maintaining proper form. If you successfully complete all 6 hangs add an additional 3% to 5% per rep in the next workout.

There are various repeater protocols that target various metabolic pathways of the forearm muscles to a greater or lesser degree depending on the hang-to-rest period used. A shorter rest trains endurance, while a longer rest trains strength. There is no ‘perfect’ hang-to-rest ratio, so choosing the best one for you involves experimentation and thinking about the kinds of hanging durations that are found on your goal climbs.

As compared to the max hangs outlined earlier, long-duration repeaters are at the other end of the strength-endurance spectrum and are basically an endurance exercise. They are best used if you do not have access to rock climbing or a gym. The protocol starts with hanging for 30 seconds and resting for 30 seconds for five sets, then increasing the hang duration and decreasing the rest duration by +15 seconds hang/-15 rest through four sets of five hangs with one minute rest between sets, to 60 seconds hanging with 15 seconds rest interval on the final set of five hangs. The intensity can be increased by using less foot support or smaller holds.

Keep in mind that actual climbing is a much more effective endurance exercise for training for rock climbing. But if for some reason you can’t climb, this is better than nothing.

Reducing the volume and/or the intensity of the climbing to facilitate a peak in performance is called tapering. But unlike a distance runner, for instance, who has their race on a set date, climbers must often be ready to perform and do their best in a short time window because of weather and other uncontrollable variables. There are a variety of ways to taper, depending on the situation. Proper tapering can involve a drop in training load of up to 50% per week in a couple of weeks leading up to a climbing trip, for instance, or a deliberate reduction in training volume two or three days before attempting a goal route or project.

Determining how much and how long to taper depends on the situation on the horizon. As a guideline, though, a proper taper should leave the athlete with an abundance of energy above and beyond what they regularly experience, overflowing with motivation to participate in their event when the time comes. One of the most common mistakes that athletes make is to try to cram extra training in as they approach their goal event.

The first of these strategies fails because adaptations come when you gradually increase the training load. A sudden shock loading with insufficient recovery will leave you flat when you hope to perform at your best.

The second strategy fails for a similar reason. In this case, you are probably in a state of near-peak performance. Your body may not have been in such a high state of tune for a long time or ever. To expect that you can continue improving even though you are already in this new peak state is why we call this mistake “getting greedy.” If you have been doing your training for the past months, there is very little you can do in these final weeks to perform better, but there are a number of things you can do that will make you perform worse.

Proper diet and nutrition are the basis for good performance in all physical endeavors. Being properly fueled for rock climbing or training for rock climbing varies greatly depending on the demands of the climbing or training day. An intense big wall free climb, for instance, requires much more energy than a day out bouldering. For the former, refueling between pitches with bars and gels can deliver the energy necessary to working muscles. For the latter, there is a greatly reduced energy demand, therefore food choice and timing are less important.

In general, a climber will want to choose foods that are easily digestible while out climbing and refuel adequately when the day is done. A climber will also benefit greatly from the metabolic flexibility that comes from fasted training. This gives mountain athletes the ability to burn fat as their baseline energy source and use carbohydrates only during higher-intensity efforts. This can prevent the dreaded ‘bonk’ that has been the culprit of many failed climbs and summit attempts.

In summary, be metabolically flexible, have sufficient fuel on board for the demands of the day, and refuel adequately when the climbing day is over.

A comprehensive analysis of the mental training that aids high performance goes far beyond what can be explicated here. However, several different practices and methods, if used regularly, can be instrumental in aiding climbing performance. The basis for all of these practices and methods hearkens back to the four stages of conscious habit formation outlined at the beginning of this article. It is only by bringing your mental and emotional states into conscious awareness that they can be either supported or replaced with more effective states of being.

Here are a few mental exercises that you can practice and apply to rock climbing performance.

The human mind is a complicated web of conditioned states arising from life experience, evolutionary heritage, and other less-understood factors. Our web of conditioned states can work for or against us in climbing, as well as in our daily pursuits.

As an example, picture the crux section of your goal climb, and visualize yourself climbing it successfully. Pay attention to how the visualization affects your emotions. Do you feel: Excited? Nervous? Calm? Fearful? Cautious? Confident? Then visualize again with the most optimal emotional state possible that would facilitate the outcome you desire. Do this many times until you feel that you know as many of the factors as possible that affect the outcome, and you successfully navigate them coolly and confidently.

Whether you fear falling, failure, or something else, you can reconcile them by visualizing the outcome you want and avoiding focusing on the one you do not. A state of optimal performance involves having a calm center of presence and awareness in the eye of the storm of all sensory and perceptual input, where the world drops away, and you are totally focused on the task at hand.

Training for rock climbing is a complex multi-variable mixture of factors.. In this article, we have only touched upon the practices you can use as a framework to build an individualized training program structured around your goals both now and in the years to come. The models, concepts, and guidelines presented here present you with the keys to steady, injury-free progress.

Training for rock climbing is complex and must be tailored to the abilities and goals of each individual climber and done consistently over days, weeks, seasons, and decades. Climbing in all of its different flavors is a rich tapestry of successes and failures, triumphs and defeats, that provide the opportunity for us to better know and understand ourselves in ways that few other activities can. Climbing is a magnifying glass under which our struggles, vulnerabilities, and weaknesses are brought into the light of day to be experienced in all their beauty and ugliness. And it is through our witnessing and navigating the beauty and the ugliness in the act of climbing that we have the opportunity to truly know ourselves.

Related Links: