Case Study: David Ayala Hardrock 100 Build

By: Andy Reed

Posted:

David Ayala recently finished the 2025 Hardrock 100 in fourth place. He was the first American, finishing behind a trio of Frenchman and ahead of numerous other world class runners. He completed the anticlockwise version of the course in the third fastest time of any American. In this article, I will highlight some of the strategies we used in David’s Hardrock build.

I think it’s important to state from the outset that David came to me as an already very accomplished trail and ultra distance runner with an impressive résumé of results in the mountain and ultra scene, including a number of FKT’s. It’s also fair to say that he flew under the radar somewhat, and was a far less well known athlete than a lot of the field. In most of the pre race reviews with race predictions, he was not even a factor.

David decided to work with me at Evoke Endurance as his coach immediately after his name was drawn in the Hardrock lottery. He had been waiting for over 10 years to get into this race and he was keen to leave no stone unturned in terms of his training and race preparation. He was happy to try some new approaches.

On race day, David’s preparation was put to the test, and he was able to execute with a really impressive performance, finishing in 24h 22m, only a few minutes behind third place.

When I first spoke to David it was obvious that he had a lot of natural talent. His ultrasignup page attests to this and it’s worth taking a look. Having said this, it seemed to me, after our initial intake call, that were was some low-hanging fruit that we could address in his build to the July race. I felt that whilst he had excellent endurance, he was perhaps lacking in the specific muscular strength needed to complete a quick loop, and that we could very likely introduce more structure and quality into a lot of his sessions, targeting efforts in and around his lactate threshold, improving his speed reserve and running economy. Strength work in the gym and also specific weighted sessions on the trails would be a staple. It was also clear that his race nutrition strategy was sub-optimal so this was on the radar from the beginning.

David did not own a smart watch and so prior training data was non-existent, but it seemed that he enjoyed long, unstructured days in the mountains. He was averaging around 60-65 miles per week. He did not take a specific rest day, unless necessary. It was a training by feel approach, but one which had certainly brought him success.

In terms of David’s strengths & weaknesses, it was clear to me that he could handle a large training load; he was relatively injury free (though he had previously had a bout of severe rhabdomyolysis necessitating hospitalization); he had easy access to mountainous terrain, living in Bozeman, MT, and was very comfortable in technical mountain terrain, and was happy to include ski touring in his early season sessions.

He is a mathematician at the University by profession, and naturally inquisitive, curious and analytical. He was keen to know the ‘why’ behind specific sessions, and naturally this led to more reflection on my end. There is definitely an ‘art to coaching’ but David was very interested in the science and the goals of various training blocks. I am immensely grateful to David. He has made me a better coach, and he made me question everything in a very analytical, but also introspective way! Despite his previous successes, he was very open to change, and he freely admitted that everything we did was very different and new.

When putting together a plan for this race, it is absolutely vital to consider the unique demands of Hardrock:

1) The altitude (average elevation is around 3400m or 11,000ft)

2) The vertical gain and loss (10,000m + or 33,000ft)

3) The extreme muscular demands (steep and long descents/climbs) – 13 times above 3700m (12,000ft)

4) The ‘relatively’ slow paces with lots of hiking given the terrain (this is not Western States)

After the lottery I had David purchase a smartwatch and HR strap. I asked him simply to log what he was doing, and to become familiar with the watch and its functions. I wanted to see what he was doing, and try to gain some valuable insights into his physiology in the first few weeks, and then begin a more structured training block January 1.

We did 2 treadmill heart rate drift tests to determine his aerobic threshold and an outdoor anaerobic threshold test to establish HR zones which I used primarily to get accurate Training Stress Score numbers, to guide training loads, rather than to guide intensity. This also established that David had an excellent aerobic base (not surprising but nice to confirm) and this really was just confirmation that there would be a lot of value in introducing more quality and speed right from the get go. He was ticking along at 6 min mile pace and was still easily in zone 2, with very little HR drift, so there was no doubt that he was fit.

Our initial speed work consisted of 1000m, 1500m and 2000m repeats – we built the volume progressively, peaking at 6 x 2000m which he ran on the track once a week. David was running these repeats at around 3 mins/km (with short 2 min recoveries). At this point I was very excited, and knew that, barring injury, and with sensible progressions, there was an excellent likelihood of a high finish at Hardrock.

My goal with this speed work was to ‘raise the ceiling’ so to speak, which would in turn improve his paces at lower intensity. This would be needed to compete with the best at Hardrock.

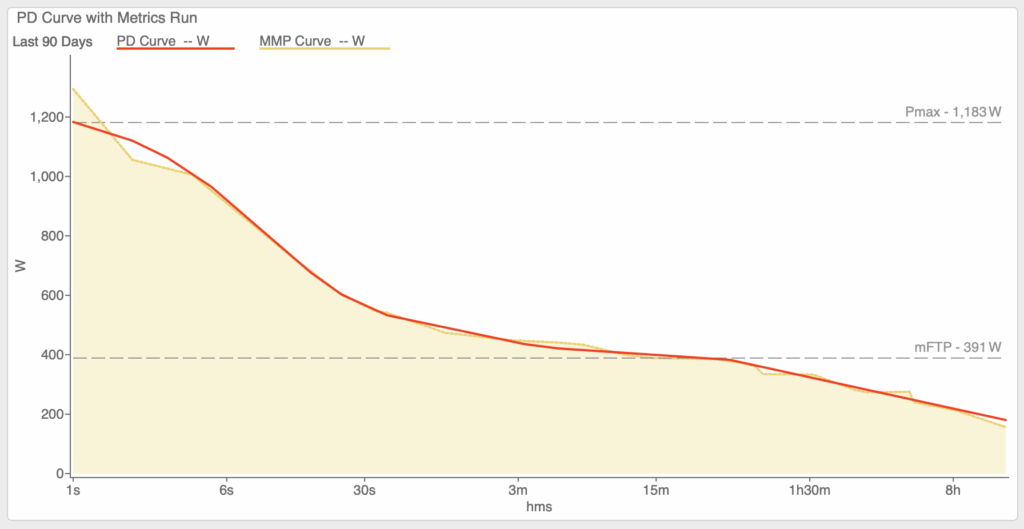

If we think about ‘raising the ceiling’ , and specifically if we think about this on a power duration curve, it is easy to see that any change anywhere on the curve will affect every other part of the curve. By pushing the left side of the curve upwards (ie by improving the more powerful, shorter duration efforts) the right side of the curve will be naturally dragged up. The pace (and effort) at all intensities improves.

The power duration curve (Fig) is a graph that illustrates the relationship between the power an athlete can sustain and the duration of that effort, showing that higher power output can only be maintained for shorter periods. Plotting power on the y-axis and duration on the x-axis, the curve starts with high power for very short durations (like seconds or minutes) and drops as the duration increases (to hours).

I also introduced uphill repeats (which were done close to anaerobic threshold/LT2) once per week, initially starting with 4 x 6 mins. By doing these repeats on a hill, it would reduce the likelihood of injury, and I also gave David the option of doing these on his skimo skis also, for the same reason.

We introduced strength work in the gym – a new stimulus for David – the now famous Evoke gym Muscular Endurance program, plus a post run core workout. We continue to see excellent responses to this type of workout, and it has become a staple in most of my mountain running programs.

I did not have a big focus on volume at this point, and in fact, this block was a significant drop in volume for David. Volume was mostly on the weekend with 2-3 hour slogs on skis or on foot in the snow. However, with a lot of quality sessions, it was important not to overcook David with too much volume, and when an athlete has years of mountain running in their legs, it takes a correspondingly large change in stimulus to get much adaptation. One has to consider ‘whether the squeeze is worth the juice’, and at this point I knew that he could easily run 100 miles. The puzzle was how to do it faster, and more volume did not seem essential.

Weekly distance peaked at 85 miles in this block, but I really just allowed the distances to look after themselves, without any specific goal mileage.

The focus moved to adding in additional mountain specific volume, and we moved the muscular endurance component of David’s strength work out of the gym and onto the trails, as the mountains started to dry out.

We have had great success, and I have seen success in my own personal training, with the addition of uphill weighted running. It’s important to realize that this carries a large stimulus, and therefore it’s vital not to overload the joints and tendons with too much, so I will typically do these sessions with water, that can be dumped before running back downhill. Once a week is plenty. The athlete fills a backpack and runs or hikes up a hill with purpose. For Hardrock I had David use poles, and where possible, he tried to maintain a running action, but the terrain would often dictate a hiking action. At the end of each interval he would dump the water and run down. We capped these sessions at 3 x 20 mins (carrying 30lbs or 14kg water). These runs were usually done on a Saturday morning, with an easy run session in the afternoon.

We kept up some intensity with strides and occasional 1km repeats but less frequently, given the additional training load. I also kept some of the uphill unweighted Z3 sessions close to AnT, but in general we started to shift towards less speed work, and more race specific intensity and terrain. David reported enjoying these sessions immensely, and he saw rapid progress as he did the weekly sessions on the same hill.

During this block, weekly distance peaked at 109 miles, with 9000m or 30,000ft + of climbing.

David talked to a Juli Bruning (a Sport Nutritionist & pro Craft team runner) during this block about his nutrition and hydration strategy. During the longer sessions David practiced fuelling. We settled on a moderately high carbohydrate intake (typically around 80-90 g/CHO per hour during training runs). This was a completely new strategy for David, as he was used to long effort in the mountains using very little in the way of calories/carbohydrates, but this worked well, and he tolerated fuelling with mostly Precision Fuel & Hydration products, and had no major gut problems. He attributes a lot of his success on race day to his fuel and hydration plan.

As we inched towards race day the focus switched to more race specific intensity and terrain. I had David perform longer back to back mountain efforts, and I gave him weekly vertical goals. So, for example, the weekly goal for the second week in May was 7000m (23,000ft). The following week was 7500m (24,750 ft). Again, I let the distance take care of itself with the main weekly goal being to spend as much time as possible, on foot, in the mountains, either hiking or running (Hardrock contains a lot of hiking) to achieve metres of climbing/descending.

I like to touch upon all intensities during all training blocks, so we did continue with an occasional hard Z3 uphill effort, strides here and there, and we did 2 of the faster flat sessions (6 x 2km with 2 mins rest) to help maintain some of that speed and running economy that David had worked on earlier in the year. It’s a case of use it or lose it, and Renato Canova has said that we should always be adding to our training, rather than subtracting, so I like to keep a little bit of everything going, although the emphasis will change to more race specific intensity domains as one approaches race day.

On that note, we did continue with some weighted uphill muscular endurance efforts, core strength work, and from time to time we had targeted ‘rehab’ sessions to deal with an occasional niggle or soreness, but David was, overall, incredibly robust throughout the build.

Towards the end of June, we used a Hypoxic tent for about 10 days, with David sleeping at 2500 – 3000m (8000-10,000ft) in the days before heading to Silverton. The goal was to arrive at least partly acclimated.

During this block David strung together multiple back to back 100 mile weeks. The biggest week was 103 miles with 31,000 feet of vertical.

The plan was always for David to spend 4 days covering the entire course on foot 3-4 weeks out from race day. This has become a very popular strategy. Last year Ludovic Pommeret had been around the course 3 times prior to race day, and ultimately he broke the course record! It’s a great chance to see the incredible beauty of the course.

Whilst it is very daunting to see what you’re going to have to cover in one big push on race day, it’s another huge training stimulus that comes at just the right time. A 100+ mile week with 10,000m (33,000 ft) of climbing, 3-4 weeks out, at a low intensity (most people hike it). David did the entire course in a fast-pack style, sleeping in a lightweight tent and staying up high at night, entirely self-supported. It gave him a chance to look at the key sections of the course. In the subsequent weeks he revisited some of these key sections, and I had David do some race pace efforts so that we could determine appropriate HR targets that would be helpful on race morning to ensure that he didn’t go out too hard, which is always the worry, when you’re at peak fitness, and well tapered.

Peak week (Softrock week) was 128 miles with 16,000m (53,000 ft) of climbing.

The following week was 68 miles, then 40 miles 1 week out. On race week he did 7 miles with a few strides prior to race day.

You can listen to David’s thoughts on his training and on how the race day unfolded, at the Evokecast #118

I don’t think that we did anything particularly ground breaking or unusual during David’s training for Hardrock. I identified some gaps, and we attempted to fill them with tried and tested methods that we have seen work over and over again. We didn’t dabble in any of the current ‘sexy’ workouts – no Norwegian Double Thresholds. We did not use a lactate meter. No heat training or sauna use. We didn’t push to the trendy ultra high carb intakes that are getting so much attention. We did use a hypoxic tent for a very short period, but this was mostly so that David could arrive in Silverton partly acclimated for his Softrock round. It’s easy to get caught up in all the hype surrounding these cutting edge methods and perhaps go hunting for the marginal gains; there is absolutely no doubt that these are fun times to be a runner, and I love to dabble in the latest technology, but at the end of the day nothing beats consistent and sensible work. Race success comes to those who embrace the work, the daily grind, and not with flashy instagram workouts.

We did not do any targeted downhill efforts, and on race day David did suffer on the long steep descents, having a lot of quadricep cramping and likely a mild case of rhabdomyolysis again. At one point in his training build I did have him start a hard downhill effort, but he tweaked his quad and adductor, so I was a bit gun-shy to do more of these, and we dropped these as I was concerned about a longer term injury. I ultimately think these may have been helpful.